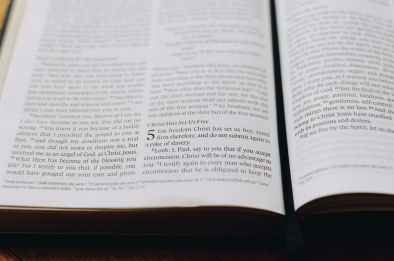

One of the key moves made during the Enlightenment that paved the way for modern historical critical study of the Bible was the decision to treat it as if it were just an ordinary book. If it is only an ordinary human book – and therefore like every other human book – it is susceptible to the same forms of analysis and treatment as any other book.

One of the key moves made during the Enlightenment that paved the way for modern historical critical study of the Bible was the decision to treat it as if it were just an ordinary book. If it is only an ordinary human book – and therefore like every other human book – it is susceptible to the same forms of analysis and treatment as any other book.

Only a few scholars can get past engagement with historical critical study these days. Discoveries of historical, cultural, and linguistic context have proved a great blessing in understanding the Bible. There has been and remains, however, a division in the western church about the quality of this modern commitment. That the Bible is a human book seems beyond doubt. It’s written in human languages. Its history is human history. It depicts humans acting like humans. Authorship of the texts that make up the Bible is straightforwardly attributed to humans. The point of division is the little word “only.” If the Bible is only a human book, a human book about what a select group of humans believes about God, that’s one thing. If the Bible is a human book for which God played a role in its creation and transmission, that’s entirely different. This contrast points at the why of reading the Bible.

If the Bible is only an ancient human book – it is ancient and it is human – than we might find it interesting; interesting in the same way we might find the works of Homer or the Wisdom of Amenemope interesting. Our interpretive activity allows us to appropriate these (and other) texts, to cull them for wisdom and insights into human ways of being.

But what if, as the mainstream Christian tradition claims, the Bible is not only a human book? What if the Bible can in at least some way be described as “the word of God” – an instance of God’s communication with humans? If this is so, then it’s worth our while to take to the time to engage with the text. This engagement takes time, something we’re often loath to give:

“God in his infinite wisdom decided to give us a book, a very long book, and not a portrait or an aphorism. God reveals himself in his image, Jesus, but we come to know that image by reading, and that takes time. God wants to transform us into the image of his image, and one of the key ways he does that is by leading us through the text. If we short-circuit that process by getting to the practical application, we are not going to be transformed in the ways God wants us to be transformed. ‘Get to the point’ will not do because part of the point is to lead us through the labyrinth of the text itself. There is treasure at the center of the labyrinth, but with texts, the journey really is as important as the destination.” Peter Leithart

Leithart would have us slow down. God’s communication with us through the Bible is not merely a list of bullet points. The purpose of engaging with the text is to engage with God and to live with God. This takes time.

I also think of Iain McGilchrist’s, The Master and His Emissary. One of McGilchrist’s claims about the corpus colossum that connects right and left hemispheres of the brain is that it not only allows the hemispheres to communicate with each other, but also inhibits communication. Slowing down the automatic processes of the brain gives us time to think things through. If the communication flow is too fast, too extensive, we will be led astray.

I suggest that if we listen to McGilchrist, we find part of the rationale for learning to read the Bible slowly. Whatever experience we have, whether that experience be of the natural world, the people around us, or a text, we always interpret that text in light of our previous experience. There is no way around this. Our initial interpretation happens automatically.

If we listen to Leithart and McGilchrist, we can hear the summons to slow down. As we recognize the automatic practices of interpretation for what they are, we can learn to question them. As Christians, we can practice intentionally bringing God into the interpretive process through prayer. Reading slowly will help us read the Bible better – and more humbly, especially as we read with others in community.

Advertisements Share this: