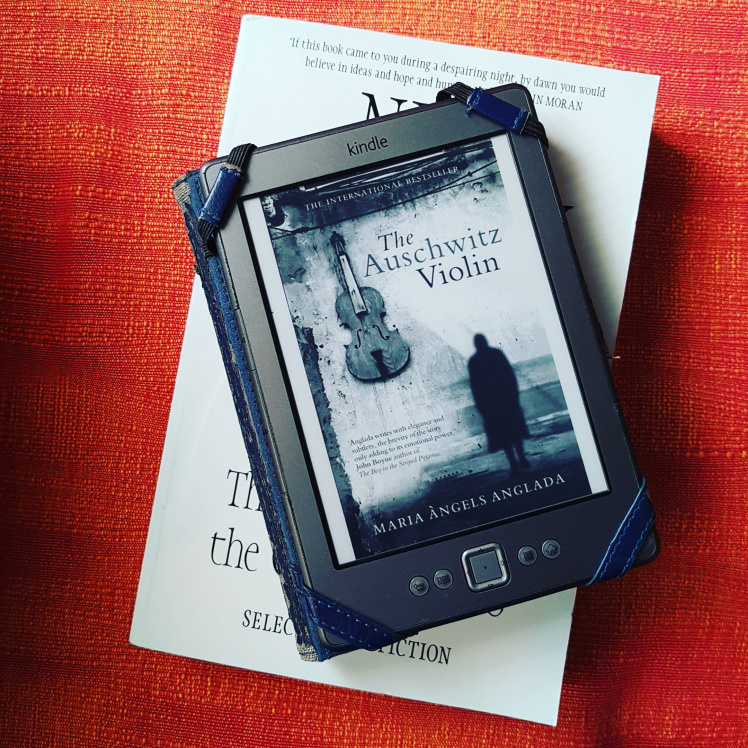

The Auschwitz Violin – Maria Angels Anglada

Originally published in Spanish in 1994

English translation in 2011 by Maria Tennent

I’d bought the Kindle version of this book a few years ago, but somehow never got around to reading it until now. When I opened it, I was surprised to see that it was only 160 odd pages – I even wondered whether the version I’d bought was incomplete!

This novella-sized story has two parallel narratives – Daniel, a luthier (violin maker) in one of Auschwitz’s concentration camps, who is ordered by his Commandant to craft a violin to the measurements of a Stradivarius, and Daniel’s niece who plays that violin at a concert in Krakow where it immediately grabs the attention of Climent, a violinist from a famous classical music trio also performing there for the 200th anniversary of Mozart’s birth. The book opens with Climent’s present-day narrative, goes into flashback for the entirety of Daniel’s story, and returns to the present at the end.

Daniel’s journey forms the narrative and emotional heart of the story, but what should have been a poignant, deep recollection falters in its execution. Holocaust stories, by their very nature, are troubling and intense, and this one is no different, but apart from the tension inherent in the circumstances, the somewhat rushed nature of the storytelling lets it down. Daniel’s a sympathetic character, but all others surrounding him were two-dimensional (even the ones in his recollections) and there were too many gaps in the details and information to render a true three-dimensional vision. What I did love were the factual details at the start of each chapter – excerpts from official reports – which gave a far less generic idea of the harrowing, human atrocities of those dark times, than much of the story. Was this lack of development intentional on the part of the writer to show the emotional and mental detachment, the retreating deep within himself consciously practised by Daniel so as to survive each day? Even so, the execution doesn’t quite succeed, and adds to the general feeling of narrative dissatisfaction. The present-day narrative appears equally rushed, less real for the minimal narrative time allotted to it as compared to the flashback, and appears no more than a crutch for the flashback, despite the strong connection that they share, and one of the central characters being in the dark about the violin’s fate as well as the fate of his friend, Daniel. In my opinion, the fact that we are already told that the violin survived takes away much of the narrative tension, though the interest in knowing the whole story remains. As a writer myself, I couldn’t stop myself from thinking about how I’d handle it, how I’d change it so that it wouldn’t read so “flat” and more cohesive. It’s important to point out that this is a translated work, and one never knows how much changed or was lost, so maybe some of the clunky, expositional prose is because of it.

Now to what I really enjoyed and wanted more of – the juxtaposition of the beauty and art of the luthier pitted against the merciless brutality of the concentration camp, the delicate, sensitive, complex nature of its treatment versus the horrors of its setting. Daniel working on the violin and the beautifully, hauntingly poetic bits of description of the process (where we could almost imagine the lilt of the original text) was, for me, the heart of this narrative, the most compelling, magical moments when Daniel steals some semblance of peace in that godforsaken environment forgetting his hunger and his own increasing frailty. There’s an additional layer when we realise that Daniel’s very reason to live, to survive another day despite lack of regular sustenance (watery turnip soup on most days) and punishments entirely dictated by the whims of the guards, has been forced upon him. He has no choice but to craft the violin when ordered to, forced to create beauty in the midst of the worst of humanity’s suffering, by the same person in charge of his and the others’ ill-treatment. He shows, by example, how it’s possible to go beyond what one thinks a human is capable of, mentally, physically, spiritually, when one finds a strong enough dream and hope to hold onto.

I’d recommend this book for that, but ultimately, for me, even those moments of beauty could not alleviate my general disappointment.

Advertisements Share this: