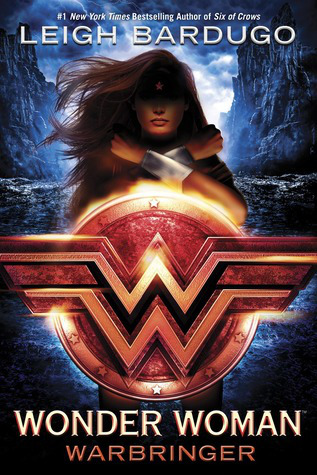

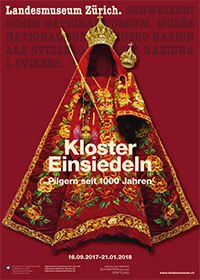

Einsiedeln Abbey, exhibition poster https://www.nationalmuseum.ch/e/microsites/2017/Zuerich/Einsiedeln.php

A striking poster advertises an exhibition dedicated to the history of 1000 years of pilgrimage to Einsiedeln Abbey, the seat of the Black Madonna. We see her red robe and the crown but the statue is not there. A veil is all there is. The energetic, blood red colour of the cape arrests and fills with awe. It dresses up the unconscious, adorns the shadow, crowning darkness and emptiness. “I am all that has been and is and shall be; and no mortal has ever lifted my veil,” – the words inscribed on the statue of Isis of Sais come to mind. All the symbolic representations of the divine are just what comes from our attempts at peering through the veil; this is why we communicate the mystery or perhaps how the mystery communicates with us. In our daily world biased towards clarity, obviousness, growth, achievement and tangible benefits, the Black Madonna is an omen of wholeness that we have lost on the way. She heals by making whole, soothes and warms the cold hearts, projecting boundless forgiveness and compassion. She is not always meek, but can be quite defiant and disruptive in relation to the stale status quo. Like the unconscious, she is the great balancing force. The weak, the sick, the disenfranchised, the disempowered, women, strangers, outsiders and foreigners, have all sought refuge under her mantle. It was believed in the earlier centuries that only the Black Madonna can show the right way to murderers and other criminals. Until the eighteenth centuries convicted criminals of Switzerland were able to atone for their guilt and go free if they made a pilgrimage to the holy statue.

The capes of the Black Madonna of Einsiedeln

There are many covert ways in which the church still try to downplay her vibrant and growing cult. Her blackness, for example, is usually explained by the prolonged exposure of the statue to candle smoke. This is quite hard to believe, since the numerous Black Madonna statues have sprung up in numerous places in the world immediately in their black glory. According to legends, the statues were often found by children, shepherds or animals close to caves or streams, often buried in the earth. The mystery surrounding their sudden emergence is symbolically very fitting. She shows herself to the humble and the weak, her source of origin being veiled in mystery. She does not seek a central or prominent role, and yet she is the centre of the mandala, the creative matrix from which all life came and to which it will return. Although her face is featured on the poster advertising the exhibition, she is just but one of the themes of it. Still, it was easily noticeable how crowds gravitated towards and concentrated in the sections dedicated to her. Disappointingly, the role of Forest Sisters, one of whom offered the statue of the Black Madonna to St Meinrad, the founder of the monastery, was not acknowledged. Nothing is said of the appalling treatment of the Sisters by the male establishment of the Monastery. Namely, they were driven out of the Dark Forest, where they lived in a peaceful community gathering herbs and healing the sick, banned from visiting the Black Madonna statue, ordered to wear black and had to lead a convent life in the nearby town (see my previous post on the subject https://symbolreader.net/2016/02/28/the-black-madonna-of-einsiedeln/). As a consolation, the sisters received a copy of the original Black Madonna statue. What is more, the lay public were also restricted by the Benedictine monks from adoring the statue right until the beginning of the twentieth century. Older female inhabitants of Einsiedeln still remember the times when they had to sneak in to the church to pray in front of the Black Madonna.

The Black Madonna of Einsiedeln

I am Black and Lovely: the Mystery of the Black Madonna by Margrit Rosa Schmid is a booklet rich in detail that accompanies the exhibition. It contains a wealth of stories about the Black Madonnas of the whole world. I was not aware of the sheer number of statues and shrines of her in Switzerland alone. At the beginning of the twentieth century in the Italian canton of Tessin, where her cult is very strong, a local pastor felt uncomfortable with what he perceived as a pagan cult of the statue of La Madonna Nera. He replaced it with a white Madonna, which sparked outrage with the locals. Eventually, the church had no choice but to give in, the Black Madonna was restored, while the white one ended up in pastor’s attic. This particular Black Madonna is a copy of the magnificent Black Madonna of Loreto in Italy. Schmid beautifully describes the symbolism of the appearance of the original Italian statue. Especially striking are the five black moon sickles adorning her gown complete with a reversed red triangle – a symbol of feminine fertility (the chalice and the womb). During the French Revolutionary Wars, Napoleon moved the Black Madonna statue from Loreto to Paris, where she was displayed in Louvre as an Egyptian goddess. He must have understood subconsciously that the Black Madonna indeed comes from a long lineage of ancient dark mother goddesses, especially but not only Isis. The Loreto Chapel of Madonna showcases statues of nine Sibyls, further strengthening the connection with the ancient cult of the goddess as well as pointing at the gift of prophecy, seeing in the dark, common to all dark female deities. Mary, not only in her role as the Black Madonna, has always fulfilled a symbolic role of a pontifex – a bridge builder between humans and divinity.

La Madonna Nera of Sonogno, Switzerlad

The Black Madonna of Loreto

A particularly moving legend is connected with the Polish Black Madonna of Czestochowa, who bears two long scars on her face. In the 15th century, the monastery was raided by the Hussites, who stole the icon. However, their horses refused to move the wagon in which they were travelling. In frustration, one of the robbers inflicted two strikes on Madonna’s face with his sword. When he tried to draw his sword upon the image for the third time, he fell to the ground and died a painful death. It is perhaps her fragility and a memento of suffering visible on her face that makes her divine form so human.

The Black Madonna of Czestochowa, Poland

Advertisements Share this: