The Book of Luelen, Luelen Bernart, 1977 (written in 1934-46)

- Federated States of Micronesia, #1

- Borrowed from SF Library

- Read January 2017

- Rating: 2/5 (BUT: this rating reflects only my reading enjoyment and is not a reflection of the inherent quality of the book. The reason for this distinction will become clear further on)

- Recommended for: ethnobotanical historians and sociocultural anthropologists

Annotations to the Book of Luelen, John L. Fisher, Saul H. Reisenberg, Marjorie G. Whiting (eds.), 1978

- Borrowed from SF Library

- Read January 2017

- Rating: 3/5

- Recommended for: as above, only more so

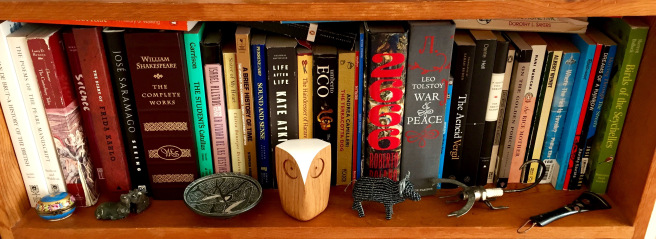

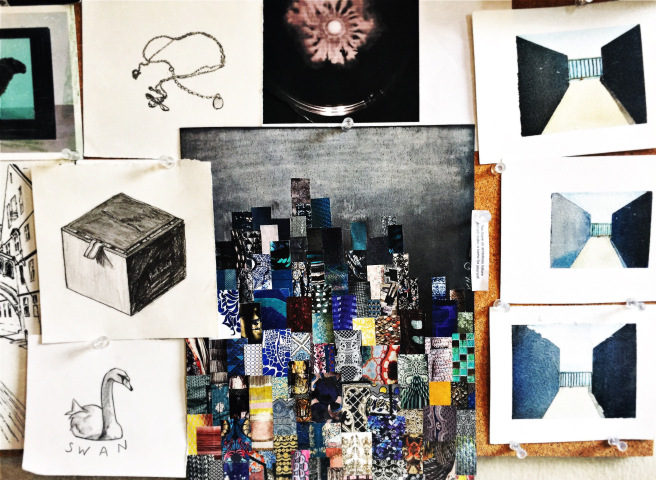

I’ve always been something of a magpie (my mom, if she reads this, will probably suggest losing the qualifier in that sentence). I have a penchant for acquisition, though I am not a completist and I rarely pursue my collecting in any sort of systematic way: I just like things. Pretty, unusual, interesting, sparkly things. I have owned a breathtaking variety of art supplies, from linoleum blocks to film developing reels to embossing powder, and I still have every paint brush I’ve ever bought. I compulsively squirrel away souvenirs from my travels, be they maps or ticket stubs or paintings by street artists. Over the years my collections have included:

- tiny seashells

- matchbooks

- decorative bowls

- small, exceedingly tacky (in retrospect) porcelain animals

- model horses

- dolls

- scraps of colorful paper

- ibid, but fabric

- ibid, but yarn

- art

- plastic cameras

- foreign coins

- and, of course, books. Always books.

With all the moving around I’ve done in the past fifteen years, my ability to collect things has been fairly limited (though apparently no power on earth can curb my impulse to acquire books and yarn; I have had to winnow these stashes for four separate international moves and every time I’m settled again they seem to proliferate of their own accord), but nothing has reined in my penchant for accumulating information. I collect ideas, facts, and stories. I love lists and miscellanies: little bits of useless data to take out and admire on a rainy day.

Given all this intellectual acquisitiveness, it seems like Luelen Bernart’s unusual book should be right up my alley. And yet I struggled with it, and ended up returning it to the library unfinished.

Luelen Bernart was a Micronesian from the island of Pohnpei, who wrote his book in the decade prior to his death in 1946. The Book of Luelen is often described as a history–the only Micronesian history written by a Micronesian–and it is, kind of, but it’s also a compendium of all of Luelen’s received knowledge, an attempt to preserve traditional Pohnpeian knowledge in a rapidly changing world. The book’s hundred short chapters (a format modeled after the Bible, which seems fairly apt for what Bernart was trying to do) include religious origin stories, ancestries, and lists of native plants. To understand what a radical act this transcription represented it is necessary to know that “on Pohnpei, as elsewhere in Micronesia, people are distinguished from one another largely by what they know. Talents vary, but one rule governs: a man cannot tell all that he knows, lest he lose that which makes him special.” Dirk Anthony Ballendorf of the University of Guam writes that Luelen Bernart was breaking violently with tradition, both by committing his personal knowledge to written form (thus making it available to a potentially unlimited audience), and by passing on so much of it in one place. In fact, after he died his descendants guarded the book carefully, to the extent that it still has not been published in the Pohnpeian language in which it was written, but only in English translation.1

So I think there is a reason that I only got through half of this book before I had to return it to the library: I am not the intended audience. The English translation, with its book of annotations, is undoubtedly a valuable resource for scholars in all areas of Micronesian research, be it history or sociology or botany. But fundamentally, Luelen’s book was meant to be consumed and understood by Pohnpeians. It was intended to preserve cultural knowledge, but not necessarily to disseminate that knowledge to outsiders. To me, a list of unfamiliar plants names is not inherently interesting; to a Pohnpeian each plant has (or should have, to Bernart’s mind) a specific meaning.

The interest that the book holds for Pohnpeians can be seen in the proliferation of illicit copies on the island. Luelen wrote his book in school notebooks and scraps of paper; he dictated the last twenty chapters to his daughter Sarihna when he was too weak to write. She compiled it all into a book, and after she died, ownership of the book passed to her husband Koropin. Koropin kept it hidden, but was persuaded to lend it to some visiting scholars so it could be photographed and translated into English (though it’s not entirely clear if he was on board with the translation part of it). The book was entrusted to one of Koropin’s compatriots to be returned to him, but it never made it back. Likewise, one of the sets of photographs (taken, incidentally, by Walker Evans) disappeared en route to its intended recipient. “There are reports,” according to Ballendorf, “that still other copies have been made.”

It’s funny. When I started to write this post, I had concluded that The Book of Luelen isn’t a book so much as a resource–a valuable resource, certainly, but not a readable text. I could easily understand the reasons that Luelen wrote his book, I thought, but it was harder for me to understand who his intended audience was. It seemed that such a book could only appeal to a handful of scholars in relatively esoteric fields. It took a bit of background reading for me to understand the cultural imperialism of which I was guilty in this line of thought; it also shows one of the many shortcomings of my approach of reading only novels and limiting my background or scholarly information about each country on my list. The Book of Luelen obviously holds great value to many people in Pohnpei and perhaps in Micronesia generally. I, lacking the context to fully appreciate this remarkable work and the information it contains, have missed out on a unique cultural treasure. I’m not saying that I have a duty to become fully fluent in Micronesian culture so that I can appreciate Luelen’s book, but it is a humbling reminder that my failure to enjoy a book from a different country may often be due to my own shortcomings rather than the work’s.

It’s funny. When I started to write this post, I had concluded that The Book of Luelen isn’t a book so much as a resource–a valuable resource, certainly, but not a readable text. I could easily understand the reasons that Luelen wrote his book, I thought, but it was harder for me to understand who his intended audience was. It seemed that such a book could only appeal to a handful of scholars in relatively esoteric fields. It took a bit of background reading for me to understand the cultural imperialism of which I was guilty in this line of thought; it also shows one of the many shortcomings of my approach of reading only novels and limiting my background or scholarly information about each country on my list. The Book of Luelen obviously holds great value to many people in Pohnpei and perhaps in Micronesia generally. I, lacking the context to fully appreciate this remarkable work and the information it contains, have missed out on a unique cultural treasure. I’m not saying that I have a duty to become fully fluent in Micronesian culture so that I can appreciate Luelen’s book, but it is a humbling reminder that my failure to enjoy a book from a different country may often be due to my own shortcomings rather than the work’s.

1. Dirk Anthony Ballendorf. “Luelen Bernart: His Times, His Book, and His Inspiration.” Micronesian Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 4, issue 1, June 2005, pp. 17-24. ↩

Advertisements Share this: