The APTS (Australian placental transfusion study) trial has just appeared on line. This was a high-quality multicenter, international RCT of immediate cord clamping (less than 10 seconds) compared to delayed clamping (60 seconds) for babies born less than 32 weeks gestation. (Tarnow-Mordi W, et al. Delayed versus Immediate Cord Clamping in Preterm Infants. the FPNEJM 2017.)

Another trial arriving almost simultaneously is a smaller trial from the UK, which compared cord clamping at less than 20 seconds to clamping at at least 2 minutes, with reuscitation staring with the cord intact in the intervention group. (Duley L, et al. Randomised trial of cord clamping and initial stabilisation at very preterm birth. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2017.) I will come back to that trial in part 2.

The benefits of delayed cord clamping for term babies are quite obvious from the RCTs, and basically show a significantly improved Hemoglobin/Iron status for the first year of life, which seems to lead to some improvement in fine motor function, in the long term, with no important down-side. The higher bilirubin levels among late-clamped babies do not lead to more phototherapy, if modern restrictive phototherapy guideline are followed.

The only real disadvantage is that it is much harder to give blood to a public cord blood bank after delayed clamping. Public banks have been the source of stem cells for bone marrow transplants for hundreds of children (and as far as I know adults as well) so this should not be dismissed…

For the preterm baby I thought that much of the evidence had been over-hyped, with claims of reduced IVH, and reduced NEC, based on tiny numbers from tiny trials, with no robust evidence of benefit, apart from higher hemoglobins, probably leading to fewer transfusions. What we really needed was a large RCT with enough power to answer questions about efficacy and safety.

The APTS trial gives that power, with over 1500 babies randomized, and, although much smaller, the trial from England is the second largest trial, with over 260 babies. The remaining trials that have been quoted as the justification for the worldwide movement for delayed clamping in the preterm, have mostly been tiny, with sample sizes between 32 and 200.

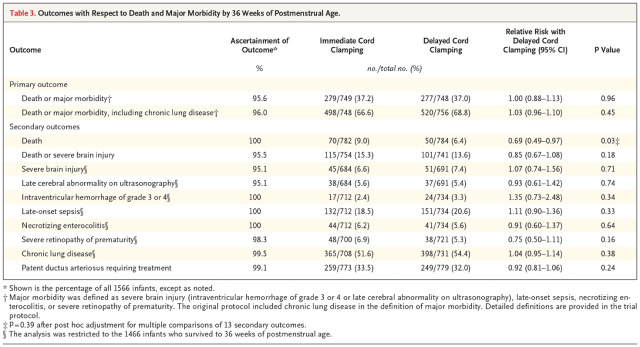

What did the APTS trial show? Speaking in the strictest sense it showed no difference between groups in the primary outcome. The primary outcome was a composite outcome of death, serious brain injury, late-onset sepsis, necrotising enterocolitis or severe retinopathy. When the study was planned bronchopulmonary dysplasia was also part of the primary outcome, but with changes in practice the authors found that the incidence of “BPD” was much higher than expected (many babies were on respiratory support with positive pressure and 21% oxygen at 36 weeks post-menstrual age), so during the trial, before the final data were analysed, BPD was deleted from the composite outcome. When you look at the individual components of the composite outcome, there is no sign of a benefit for any of the components of that composite, except one, that is mortality.

When only one part of a composite outcome is positive, but it is much less frequent than the remaining parts, the overall composite may well be negative. This is one of the problems with composite outcomes, you can actually lose power for the most important part of the composite, whereas these composites are usually being used to try to increase power!

The outcome of death should therefore strictly be considered to be a secondary outcome, and therefore treated with some scepticism. I’ll come back to this point.

Also important is the fact that 26% of the delayed clamping group did not get 60 seconds of delay, which was most often due to concerns about the neonatal status (70% of the time). This was unavoidable given the design, as most centers were not resuscitating babies with the cord intact. 20% of the delayed clamping group got the cord clamped before 30 seconds, the other 6% who did not follow protocol it was between 30 and 60 seconds.

It would be interesting to have a “per-protocol” analysis of mortality results, which I would guess would show a greater difference between groups, as babies who had the delayed clamping interrupted because of concerns about neonatal status might well have a higher mortality. There is an analysis of the per-protocol effects on the primary outcome (in the supplementary appendix) which shows a difference (which may just be due to chance, p=0.2) : 37% with immediate clamping, and 33% with delayed clamping, but no mention of the components of that outcome.

There is also a report of the causes of death in the supplementary appendix, causes which cover the entire range of causes of death among very preterm babies. The biggest single cause was septicemia, which was also the cause that showed the biggest difference between groups, 2.2% immediate clamping, and 0.5% delayed clamping.

There is also an analysis in detail of head ultrasound findings which show no tendency to be different in any aspect between groups.

Finally there were many fewer babies who needed blood transfusions with the delayed clamping (61% with immediate clamping, 52% with delayed clamping) but more babies with polycythemia (2% had hematocrit >65% with immediate clamping, 6% with delayed clamping, 1% over 70% immediate, 2% with delayed). There was no clinically important difference in bilirubin concentrations (mean was 3 micromoles higher with delayed).

Overall then, a potential decrease in mortality, a decrease in the number of babies receiving transfusion, with a very small increase in polycythemia, which was probably not due to chance (p<0.001).

What to do with these results? Well, as yet there is no signal for a clinically important harm of delayed cord clamping; with the proviso that babies who are intended to have delayed cord clamping may often have the cord clamped early. I think that a clinical approach planning for delayed clamping at, or perhaps after 60 seconds, is consistent with the best evidence, it will decrease the number of babies receiving transfusions, and might decrease mortality.

We also need an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. But for that you will have to wait for part 3!

Share this: