Music underwent some drastic shifts in the last century, with its cultural earthquakes, wars and revolutions. Social systems broke down, and with them cultural institutions splintered: 20th century music is a history of shards, and this is what Alex Ross traced in his best selling narrative, The Rest is Noise. This book is the inspiration behind the festival running at the Southbank Centre, which certainly deserves our attention.

Shedding light on our recent history, Mikhail Jurowski and the London Philharmonic presented three works from composers who had lived and written under the Soviet regime: Gyorgy Ligeti, Witold Lutoslawski, and Alfred Schnittke.

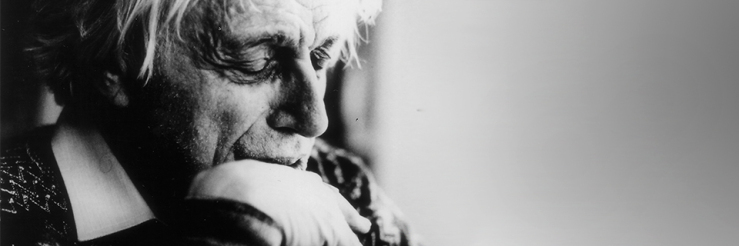

Ligeti’s (above) Lontano came as a glance into the abyss: almost a wordless chorale. Its opalescent harmony submerged us in a pensive, spectral soundworld.

The orchestra were joined by German-Canadian cellist Johannes Moser for a bitter rendition of Lutoslawski’s Cello Concerto, commissioned by Rostropovich. The cello battles the orchestra, with its sinuous stealing of themes and oppressive dynamic. Sections of the concerto have no bars or beats: then the players must take their orders from the conductor. Moser’s performance was wonderfully vibrant, mordant, acerb and bitterly tragic.

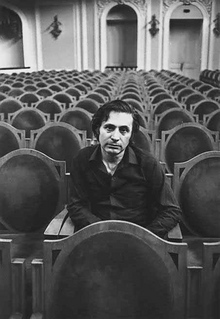

A pupil of Shostakovich, Alfred Schnittke became a figure of the anti-establishment culture that grew at the downfall of the USSR. Attending concerts of his music was seen as dissident: Soviet strictures on music were ruthless. Jazz was decadent and bourgeoisie, atonality seen as an offense to solidarity: by comparison, Schnittke’s mighty First symphony is punk, and flouts it.

The orchestra files onstage like factotum to shrieks from the tubular bells (special mention goes to a tuba player who literally danced on). Schnittke’s (left) was a “polystylistic” style, gleaned from his composing for film: he steals from disparate genres like a magpie. Chorales, classical symphonies, Mahlerian recitatives and funereal serialism rub shoulders with a Jazz band, waltzes, tangos and military marches, all mashed together. There are titters of laughter; the wind section “dies”, walks offstage, is resurrected, and dies again; only one violinist, playing from Haydn’s Farewell Symphony, is left on stage. Schnittke claimed that he’d set down a chord and watch it dissolve under his fingers: disintegrating, disjointed lines of music contribute to mounting insanity, a real symphony of the absurd. It was performed with panache that drew bouts of laughter.

If we reply with a raised eyebrow or a despairing grin, this music surely deserves our attention, and the concert was a performance to remember, played with sincerity and humou. These pieces, a secret diary from behind the Iron Curtain, left me exhausted but enlivened: sometimes we need a certain vitriol to freshen our vision.

30.08.13

the photo caption for this article is the Soviet War Memorial, Budapest

Advertisements Share this: