We have been to see the sea. We see it fairly often in any case but this time it was for a long, hard look, the window of the sitting-room of the rented apartment giving straight out onto the smaller beach and a wide view of the sea.

We are, of course, acquitted of the need to fashion trenchant or memorable remarks about it. It has all been done so many, many times before. ‘MER: N’a pas de fond. Image de l’infini. Donne de grandes pensées,’ Gustave Flaubert wrote, a hundred and fifty years ago, in his posthumously published Dictionnaire des idées reçues. Bottomless, a symbol of infinity, prompting deep thoughts.[1] That more or less covers it.

The fact is that gazing at a calm sea or, indeed, a restless one, is as transfixing as staring into an open fire, far more so, in fact. I might have added ‘watching other people work’ but this is often oddly gender-specific: men will watch for hours while other men dig a hole but perhaps they are ex-diggers themselves, so the watching is simply an exercise in nostalgia. Certainly, I can regard the open sea for a considerable period of time without strain; and have seen innumerable other people—regardless of gender—doing the same.

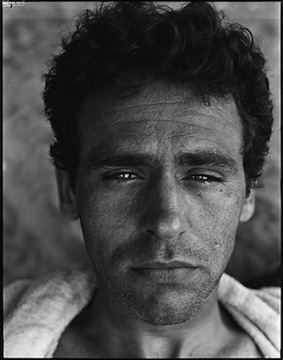

(© Walker Evans, 1937; via Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Writing of summer evenings in Knoxville, 1915, James Agee describes at length ‘the fathers of families’ all ‘hosing their lawns.’ After closely describing the varied sounds emitted by the hoses, singly and in concert, and then the dwindling and final ceasing of such activity, he notes that the locusts ‘carry on this noise of hoses on their much higher and sharper key.’ There is, again, the doubled effect, of the individual and the choral:

‘They are all around in every tree, so that the noise seems to come from nowhere and everywhere at once, from the whole shell heaven, shivering in your flesh and teasing your eardrums, the boldest of all the sounds of night. And yet it is habitual to summer nights, and is of the great order of noises, like the noises of the sea and of the blood her precocious grandchild, which you realize you are hearing only when you catch yourself listening.’[2]

That wonderful sentence is echoed for me, in another book published that same year, Lawrence Durrell’s Bitter Lemons, in which he stands with the Hodja (teacher) as darkness falls over the sea. ‘It was a blessed moment—a sunset which the Greeks and Romans knew—in which the swinging cradle-motion of the sea slowly copied itself into the consciousness, and made one’s mind beat with the elemental rhythm of the earth itself.’[3]

That ‘great order of noises’ evokes for me a faint tang of the divine, as of a religious order, which may not be fanciful, since religion played a significant part in Agee’s development: from the age of about ten, he lived for years in the dormitory at St Andrew’s School, established by Episcopal monks of the Order of the Holy Cross. His short novel The Morning Watch is set in such an institution, and centres on the thoughts and emotions of a young boy, Richard, in the early hours of Good Friday.

‘Knoxville: Summer 1915’ now stands as a brief prologue to Agee’s major novel, A Death in the Family. The central event, the death of the father in an automobile accident, is drawn from Agee’s boyhood: his own father died in just that way when James was seven. It’s an uneven but often very powerful book. The unevenness, or variations in control, focus and intensity, derive in part from the fact that Agee did not live to effect final revisions, which means, on occasion, that choices haven’t been made and words or phrases overlap and blur into one another. Then, too, the first editors chose to italicise sections of the book which they feel are not strictly part of the story: these are the reflections of the boy, Rufus, but it’s highly problematic to decide what is or is not ‘part of the story’ when that story largely comprises an intense recall of the events and its consequences: psychological, emotional and religious. The italics, anyway, are a little disconcerting at first – though only at first – recalling Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Agee explores the reactions (and fears and repressions) of several members of the extended family, sometimes with a startlingly close-up, penetrative stare. Not formally perfect then, not aesthetically neat, but very effective, often strong, sometimes delicate.

Agee worked on A Death in the Family for several years from the late 1940s. When he died in 1955, it was completed, with the addition of ‘Knoxville : Summer 1915’, by the editors at McDowell, Obolensky (Agee’s friend David McDowell, was one of the co-founders), who also produced books by Hugh Kenner and William Carlos Williams, among others. Published in 1957, Agee’s novel won the Pulitzer Prize the following year. The University of Tennessee Press published a scholarly edition of the ‘restored’ manuscript ten years ago, edited by Michael A. Lofaro, professor of American literature and American and cultural studies at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

There’s a nice photograph by Helen Levitt, dating from 1939, which sat on my desktop for a while: Agee sitting at the wheel of his convertible beside his second wife, Alma, with, in the back seat, the young Delmore Schwartz.

Walker Evans Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art © Estate of Helen Levitt (1913-2009)

Clouds of cigarette smoke, inevitably, drift up from the front seat; and all three are facing forward, Agee in what looks like a corduroy cap, Schwartz with his intent, distinctive profile; Alma, with her headscarf slipping back a little, gazing slightly down and, perhaps, inwards, maybe already sensing trouble to come. Here’s another photograph of Alma, by the great Walker Evans, taken in Brooklyn in 1939.

Walker Evans Archive, 1994 © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Evans took the photographs which are so integral a part of the classic book he produced with Agee, published as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (included in the Agee volume together with A Death in the Family and Agee’s shorter fiction: his novella The Morning Watch and a handful of short stories).

Much of Agee’s creative energy went into his film criticism (and co-writing the screenplay for The African Queen; he wrote the script for Charles Laughton’s 1955 The Night of the Hunter too, though Laughton cut it substantially). Agee also adapted ‘The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky’ by Stephen Crane. He appeared in a minor role in the film, which was released in a two-part Face to Face, the second section being an adaptation of Conrad’s The Secret Sharer.

That last detail interests the Ford Madox Ford scholar, because of Ford’s very specific allusions to Crane’s story,[4] and because several commentators have seen in Conrad’s novella evidence of his complicated attitude towards the collaboration with Ford (which produced two full-length novels and a long short story) and its ending.[5]

When her marriage to Agee broke down, Alma moved to Mexico with their young son, Joel; then back briefly to New York, then Mexico again, where she finally married the writer and political activist Bodo Uhse. She had some interesting encounters while working in a Mexico City Gallery, coming to know Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros and Pablo Neruda. In 1948, Alma, Bodo and Joel moved to East Germany. Joel later wrote a memoir called Twelve Years: An American Boyhood in East Germany (2000), published by the University of Chicago Press. Also for Chicago, Joel Agee has translated from German a number of volumes by writers including Rilke and Hans Erich Nossack, but principally, Friedrich Dürrenmatt: The Pledge, The Assignment, The Inspector Barlach Mysteries and the three-volume Selected Works.

Alma lived into her mid-sixties, dying in 1988: her memoir, Always Straight Ahead, appeared in 1993. But one striking fact about Agee’s generation of writers is how many of them failed even to attain that age. Agee himself died at 45, suffering a massive heart attack in a New York taxicab, while Delmore Schwartz died in a shabby hotel at 52. Weldon Kees was 41, John Berryman managed 57, and Robert Lowell 60. The slightly older R. P. Blackmur died – very slightly older – at just 61.

References

[1] Published in 1913: Robert Baldick’s translation of The Dictionary of Received Ideas is included in the A. J. Krailsheimer translation of Bouvard and Pécuchet (London: Penguin Books, 1976).

[2] James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, A Death in the Family, and Shorter Fiction, edited by Michael Sragow (New York: Library of America, 2005), 470, 471.

[3] Lawrence Durrell’s Bitter Lemons (London: Faber and Faber, 1957), 240.

[4] See Ford, Thus to Revisit (London: Chapman & Hall, 1921), 108; and, particularly, ‘Stevie and Co.’, in New York Essays (New York: William Edwin Rudge, 1927). 29.

[5] See Frederick R. Karl, Joseph Conrad: The Three Lives (London: Faber and Faber, 1979), 673; letter from Thomas C. Moser, quoted in Zdzisław Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Chronicle, translated by Halina Carroll-Najder (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 361; Max Saunders, Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life, two volumes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), I, 149.

Share this: