“We’re all citizens of a different town now. A place with its own special rules and its own special laws. A town of people living in the sweet hereafter.”

The Sweet Hereafter is a somber, reflective film. There are powerful moments, but its power comes mainly from its simmering, what many would call a slow burn. Its characters are in pain, but they press forward with an uncertain but resilient force that makes for truly compelling drama. This is my first encounter with director Atom Egoyan, and I look forward to exploring more of his work, as this was one of the most personal movies I’ve seen in a while.

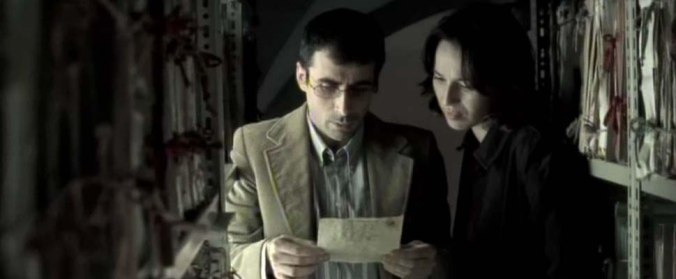

The film follows a small Canadian town after a gruesome accident leaves fourteen children dead from a school bus run off the road. Lawyer Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holm) arrives in the town and starts knocking on doors, gathering support for a class action lawsuit. We see him not as a sleazy ambulance chaser nor as a compassionate advocate of justice. He’s somewhere in the middle, but he’s definitely an outsider to these people. Stephens’ daughter is a drug addict with no hope for recovery, allowing him to connect with the townspeople on a personal level, viewing his own daughter as dead in a sense, uncertain of who she is anymore. The film seems most interested in the town’s mixed feelings over Stephen’s lawsuit and how its residents hope to move forward with their lives following the tragedy.

Sad things happen throughout the movie, but Egoyan is keen on showing us the despair that occurs between these moments of action. The film doesn’t show the car accident until the middle of the film, and it’s not too dramatized in its depiction, because that’s clearly not the point. We spend time with a good number of the town’s residents who have been affected by the accident, and many of them become significant movers in the final outcome of the film. Nicole Burnell (Sarah Polley), a young woman who survived the accident, is perhaps the film’s most dismal character, forcing the story into its conflicted conclusion with what I viewed as a triumphant decision.

The movie’s structure seems effective given its subject matter and muddled narrative. Events are presented non-linearly, but the film doesn’t dwell on this mechanic for any cheap effect. Events flow seamlessly, and the distorted timeline is only there to present character arcs in the most effective fashion. One character stands out as a villain, but he isn’t the antagonist, as Egoyan is far too interested in gray area than to give us a tangible conflict. Much of the movie is about placing blame, but a central problem is that there’s really no blame to place, and this generates frustration for a number of characters.

The structure also works with the visual aesthetic, a well-lit but mundane depiction of a quiet snowy town that could drive a person mad with its emptiness. (I was reminded of The Last Picture Show in this sense.) There are few attempts at humor, although when they land, they are spot on. Sarah Polley has a great line right at the climax of the film that serves as a much-needed release of tension. For the most part, though, The Sweet Hereafter is lulling and deceptively tragic, pelting you with small moments of despair as you search for some good fortune to cling to. Just as the snow seems to weigh down the roofs of cars and houses of the town, it weighs down its residents, only compounding their melancholy and rubbing salt in open wounds.

This movie was a unique, entertaining surprise, although a dark one at that. I probably won’t return to this movie for a while, but it’s a triumph of filmmaking nonetheless. Coupling small town mundanity with stinging personal tragedy, The Sweet Herafter really hits its mark, showing exactly how to handle gray area in narrative cinema, by embracing it uncomfortably and unflinchingly.

Films Left to Watch: 872

(The 1001 List has updated again, setting me back a few more films.)

Advertisements Share this: