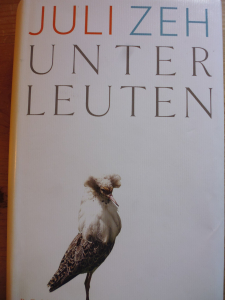

This great novel by Juli Zeh is set in the village of Unterleuten in Brandenburg,  one of the former East German Bundesländer. Situated as it is about one hour’s drive north of Berlin Unterleuten seems an ideal spot for Berliners weary of the city and seeking the authenticity and simplicity of rural life. The attempts by the newcomers to understand and integrate into village life constitutes one of the themes of this novel and indeed the clash between town and country is nothing new in literature. However here the narrative is played out in an area which has seen massive social, political and ideological changes in the preceding century, most recently the post war Communist era of the DDR ( Deutsche Demokratische Republik) and the change ( die Wende) brought about by the fall of Communism from 1989. The village of Unterleuten, as everywhere else, has seen its fair share of winners and losers from these upheavals- and the resulting grudges and resentments add ballast to the mix of emotions and rivalries bubbling away beneath the surface. The novel’s structure and crime thriller elements invite the reader to try to make sense of these subcutaneous ripples and in particular an accidental death which happened 20 years previously.

one of the former East German Bundesländer. Situated as it is about one hour’s drive north of Berlin Unterleuten seems an ideal spot for Berliners weary of the city and seeking the authenticity and simplicity of rural life. The attempts by the newcomers to understand and integrate into village life constitutes one of the themes of this novel and indeed the clash between town and country is nothing new in literature. However here the narrative is played out in an area which has seen massive social, political and ideological changes in the preceding century, most recently the post war Communist era of the DDR ( Deutsche Demokratische Republik) and the change ( die Wende) brought about by the fall of Communism from 1989. The village of Unterleuten, as everywhere else, has seen its fair share of winners and losers from these upheavals- and the resulting grudges and resentments add ballast to the mix of emotions and rivalries bubbling away beneath the surface. The novel’s structure and crime thriller elements invite the reader to try to make sense of these subcutaneous ripples and in particular an accidental death which happened 20 years previously.

The immediate narrative is around the plan to build a wind park with 10 wind turbines on an area of land in Unterleuten called ‘die schiefe Kappe’. Responses to this in the village are mixed, but there is no doubt the plan will go ahead- it is part of Angela Merkel’s new energy policy of 2010 to go over wholesale to renewables and the only question is, whose land will it be built on and who will benefit from it? The company Vento Direct requires a site of 10 hectares. The landowner Gombrowski owns 8 hectares, the Bavarian property speculator Meiler also owns 8 hectares and it is newcomer to the village Linda Franzen who owns 2 hectares and the balance of power.

Prior to Vento Direct presenting their proposals at a village meeting we have been introduced to some of the key players. Gombrowski is the proprietor of Ökologica GmbH, a farming business which had been a family business originally and was forced to convert to a collective farm under communism. The business is not now doing so well financially and clearly he would benefit from the leasing of his land to Vento Direct. Meiler is a property speculator from Bavaria who randomly bid for and won some land in Unterleuten in an auction. He is indifferent to wind turbines at first, though later wishes to have them on his land to raise money to finance his son’s drug habit. Linda Franzen is renovating her house Villa Kunterbunt and wishes to extend the property to develop her business as a horse whisperer ( aka horse psychologist) and to stable her own beloved stallion Bergamotte. She has her eye on 4 hectares of land behind the house presently owned by property speculator Meiler and may do a deal, selling her 2 hectares on ‘schiefe Kappe’ to him in return for the 4 hectares behind her house.

Now I did call the wind turbines plan the ‘immediate narrative’ and though the machinations between the characters is indeed entertaining, this narrative thread is also a hook on which to explore other themes and human reactions in this rural community. Indeed the novel does not open with the wind turbines story but instead with a witty account of the gap between rural idyll and reality in the story of Gerhard Fließ, a former sociology lecturer from Berlin, his young wife Jule and their baby Sophie. They left Berlin in search of the good life and we find them sitting indoors with the windows closed on account of the insufferable smell and smoke from their neighbour who runs a car repair shop burning rubbish on their boundary day and night.

Like Gerhard, we soon learn that conflicts are not resolved in this community by going to the authorities: Gombrowski’s friend, Hilde, has been attacked by villager Kron, but calling the police is not an option. Gombrowski claims disingenuously that disputes in Unterleuten can be settled over a drink and a chat in the local, whereas we gradually learn in a slow drip effect through the narrative that his influence is coercive and far reaching and if disputes are not settled to his liking there will be consequences for those who dare to cross him. One challenge for Linda Franzen, and the newcomers in general, is uncovering the web of power relationships simmering beneath the surface, in order to pursue their goals or simply to live a decent life. The way in which they react to and accommodate these unwritten rules provides both humour and unease- and Zeh’s skill lies in often provoking both at the same time.

To what extent are these conflicts the result of the political system under which the community lived for 40 years- the DDR? We know that Gombrowski’s 50 year dispute with Kron has political differences at its origin: Kron, a Communist, was amongst a group which forced Gombrowski’s family farm to become a collective farm under Communist rule. Gombrowski, however, did well out of the Wende-when his farm was converted to Ökologica GmbH, he was awarded a 70% shareholding and got rid of the workers’ committee. Gombrowski’s used his power at that time to ‘help’ other losers-when Arne Seidel, the vet at his farm, was not able to work because his East German qualifications were not recognised, Gombrowski supports him in becoming mayor- on the basis that Gombrowski’s projects were waved through on the nod. So Gombrowski’s ‘support’ for Arne and other villagers comes at a price and this exertion of power creates resentment, bitterness and clan warfare which tips over into violence with great regularity.

Other conflicts in the novel are brilliantly delineated, for example the generational differences. The digital generation who work for themselves, like Linda and her husband Frederik, are objects of curiosity for the older generation and there are some humorous observations, from former East Germans, about the young people’s precarious jobs and the ubiquity of surveillance cameras in the workplace! Juli Zeh brings out these differences in several powerful scenes in which characters from utterly different worlds confront one another.When Meiler arranges to meet Linda at the Hotel Adlon in Berlin, he is expecting her to be intimidated by his familiarity with the pretentious setting. Instead she is as adept as he is at dealing with both the setting and the negotiations despite her youthful ponytail and casual clothes.

The structure of the novel itself expresses difference. Each of its 62 chapters is headed by the name of a character and through inner monologue and free indirect speech both progresses the narrative, while giving us that character’s back story and perspective on events. It is to Juli Zeh’s great credit in her skilful use of voice that we are quickly drawn into the intimate thoughts of characters quite unlike ourselves and find ourselves seeing things from their point of view and even empathising with them. Yet as the novel progresses we realise that we are being told different versions of events, according to the character narrating, and that the characters themselves are unreliable narrators, being self delusional, opinionated, believing what fits their preexisting prejudices as well as just plain forgetful. In trying to piece together what happened in the past through the different narratives we sometimes feel the sands of Brandenburg are as shifting and unreliable as they seem to Meiler on his first visit to Unterleuten.

And the sands, the land itself has both an overt and symbolic presence in the novel. On the one hand it’s a story about wind turbines and the ownership of land in Brandenburg. On the other hand there are several references to what lies beneath which have a symbolic resonance. Gombrowski refers to the village’s scrap metal buried beneath the ground in DDR times rendering the soil poor and unyielding, as if the tired old grudges of the communist era are responsible for the malfunctioning community of today. His final act, which I shall not spoil, is a malicious act also concerning the land. Yet this is not the last word. That which is buried can be dug up and defused- the land can be fertilised and restored. And it is the younger generation who will do this. The newcomers to Unterleuten, renovating their properties, take up the linoleum laid in DDR times to reveal the tiles beneath, as if raking up the past and getting rid of it. And the epilogue sees the younger generation in the character of the sympathetic Kathrin take on the role of mayor as the old men die out.

This is a great novel about life in a rural community and the complexity of relationships which it reveals may be seen in smaller rural communities in many different parts of the world. Jon McGregor’s latest novel Reservoir 13 discussed here on Open Book indicates that this is a current topic of interest to novelists. Yet the setting in Unterleuten of a village in the former DDR, where sophisticated Berliners rub shoulders with the locals makes this a very contemporary commentary on life in Germany today. It is a big book in its range and breadth of characters, at times humorous, satirical, poignant and chilling and its clever plotting kept me gripped to the end. Have a look at the Unterleuten website to learn more about the characters and their community. Cross your fingers for an English translation soon and give it to your friends.

entified as ideal land for her business is owned by Meiler, a property speculator from Bavaria. He bought the land cheaply in auction, oblivious to the resentment he’s caused- his speculating will inflate land value and increase interest repayments for the locals.

The two most powerful locals make their entrances early on : Kron and Gombrowski, both older men now in their 60s who have lived in Unterleuten most of their lives. Gombrowski has a farming business, Ökologica GmbH, now not doing so well financially and it is suggested in a sort of slow drip fashion that his influence and power is both subtle and far reaching- he helped Schaller set up his auto repair yard, for what? we wonder but have no clues as yet. The fact that Kron and Gombrowski are at logger heads is seen by the fact that Kron has attacked Gombrowski’s friend Hilde. Again, there is no question of involving the police and we are told their enmity goes back a long way: Kron was an active communist and fought against Gombrowski all those years ago when he was resisting the collectivisation of his family farm. The men hate one another and their feuding is characterised by violence, some of which forms part of the narrative, some merely hinted at for the reader, but contributing nevertheless to the atmosphere of fear and anxiety which builds up during the story.

The structure of the novel enables us to meet the many characters and hear their back stories before the narrative really gets going. The chapters are each headed with the name of a character- and I loved the generational difference noted in the female characters’ ‘Gombrowski geb. Niehaus’ but ‘Kron-Hübschke’. Each chapter then describes events from the point of view of that character and here we see Juli Zeh’s skill in the range of voices she expresses-from that of the older man Gombrowski, deluding himself that he has only done good for his community and that he loves his woman folk whom he bullies and beats, to that of the cool and calculating Linda, her busy thoughts running along her demanding daily schedules, interleaved with nuggets of wisdom from her guru Manfred Gortz. In this way we see events from one individual’s point of view and, after a while inevitably become aware of the discrepancies and different interpretations put upon events by different characters and factions. And this is indeed part of the novel’s message, indicated by the mayor Arne at the end- that the really dangerous people are those who think they are right.

Advertisements Share this: