I just finished Arnold Bennett’s These Twain, the third in the Clayhanger trilogy, set in his fictitious Five Towns, based on the six towns in the Potteries district of Staffordshire where Bennett grew up.

I just finished Arnold Bennett’s These Twain, the third in the Clayhanger trilogy, set in his fictitious Five Towns, based on the six towns in the Potteries district of Staffordshire where Bennett grew up.

Well, I’m done, I thought with satisfaction the other night. I read the first two books in June 2016 and only now got around to These Twain, which was a much slower, choppier read.

Except my e-book copy (my on-the-go back-up to the paperback editions) claims Clayhanger is a tetralogy, not a trilogy. It includes a fourth novel called The Roll-Call, which is set in London, not the Five Towns, so I’m skeptical.

I trust the information on the Penguin jacket copy and bios. It says “The Clayhanger trilogy.” Three is a magic number.

But I did very much love the first book, Clayhanger, a bilidungsroman. Bennett tells the story of a middle-class hero, Edwin, the bookish son of a successful printer. Edwin hopes to become an architect but goes into his father’s business because he does not want to disappoint his father. One wonders if he’ll ever marry: finally he meets Hilda Lessways, a charming, cultured young woman who is unlike anyone he has met.

But courtship is a rocky road when you don’t live in the same town. In the second novel, Hilda Lessways, we see the same events from Hilda’s point of view, but Hilda’s passions lead her into the arms of George Cannon, who turns out to be a bigamist. While he is in prison she raises their child alone, and runs a boarding house to make ends (barely) meet. But she and Edwin meet again, and she tells him the whole story. Edwin understands Hilda’s strengths and weaknesses. They get married.

But courtship is a rocky road when you don’t live in the same town. In the second novel, Hilda Lessways, we see the same events from Hilda’s point of view, but Hilda’s passions lead her into the arms of George Cannon, who turns out to be a bigamist. While he is in prison she raises their child alone, and runs a boarding house to make ends (barely) meet. But she and Edwin meet again, and she tells him the whole story. Edwin understands Hilda’s strengths and weaknesses. They get married.

In These Twain, my least favorite, Arnold portrays their tumultuous marriage. Hilda is still half in love with her bigamist first “husband,” George Cannon. In a harrowing scene, she actually glimpses George during a tour of the prison. Hilda is moody, manipulative, and mercurial: she begs Edwin to buy her a horse and carriage, then uses the carriage to take him and and a neighbor on Christmas day to a country house she wants him to buy. That’s almost too much even for Edwin. Near the end Arnold assures us that Edwin doesn’t mind indulging Hilda’s little foibles. He adores Hilda, and she sometimes impulsively loves his practicality and kindness. But can this very ill-suited couple be happy? Who am I to say that is not the stuff of a good marriage?.

In These Twain, my least favorite, Arnold portrays their tumultuous marriage. Hilda is still half in love with her bigamist first “husband,” George Cannon. In a harrowing scene, she actually glimpses George during a tour of the prison. Hilda is moody, manipulative, and mercurial: she begs Edwin to buy her a horse and carriage, then uses the carriage to take him and and a neighbor on Christmas day to a country house she wants him to buy. That’s almost too much even for Edwin. Near the end Arnold assures us that Edwin doesn’t mind indulging Hilda’s little foibles. He adores Hilda, and she sometimes impulsively loves his practicality and kindness. But can this very ill-suited couple be happy? Who am I to say that is not the stuff of a good marriage?.

The fourth book, The Roll-Call, is the story of Hilda’s son George (Edwin’s stepson) working as an architect in London. Now it may or may not be good, but it’s not a Five Towns book, and is not on my priority Bennett list.

Has anyone read The Roll-Call? What’s your favorite Bennett? Does anyone read him anymore?

Bloggers love to plan their Autumn Reading. Well, some do. Here are some books I’ve recently added to my TBR, though I won’t get to these this year–I don’t even have copies yet! And some have not yet been published.

1. John Banville’s Mrs. Ormond. Naturally I must read Mrs. Ormond, a sequel to Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, penned by Booker Prize winner John Banville. Kirkus Reviews says,

1. John Banville’s Mrs. Ormond. Naturally I must read Mrs. Ormond, a sequel to Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, penned by Booker Prize winner John Banville. Kirkus Reviews says,

Fans of John should deem it marvelously Banville-an in its observations, humor, and insight—though they may wonder at this literary diversion by a writer who already plies the pen name Benjamin Black.

A sequel that honors James and his singular heroine while showing Banville to be both an uncanny mimic and, as always, a captivating writer.

It won’t be published here till November, and, no, it’s not available from Netgalley. (I just checked.) But perhaps I’ll find a used ARC, or will find it under the Christmas tree–put there by me.

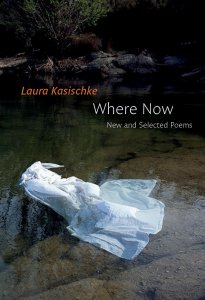

2. Where Now: New and Selected Poems by Laura Kasischke . This was on the National Book Awards longlist, and the poems I’ve found online are breathtaking. I don’t have a copy of this book yet–perhaps for Christmas?–but I love the following poem.

2. Where Now: New and Selected Poems by Laura Kasischke . This was on the National Book Awards longlist, and the poems I’ve found online are breathtaking. I don’t have a copy of this book yet–perhaps for Christmas?–but I love the following poem.

Ubi Sunt?

In the mirror, like something strangled by an angel—this

woman glimpsed much later, still

wearing her hospital gown. Behind her—mirrors, and

more mirrors, and, in them, more cold faces. Then

the knocking, the pounding—all of them wanting to be

let out, let in. The one-way conversations. Mostly not

anything to worry about, really. Mild accusations, merely.

Never actual threats. (Anyways, what could they possibly

do to you now from inside their locked, glass places?)

Still, some innocent questions on some special occasion

might bring it all back to you again, such as: Might

you simply have forgotten where you left me when you left me?

Or—Shouldn’t you be searching all the harder for me then?

Or—the question that might frighten any woman being

asked this of her own reflection (no

tears on its face, a smile instead)—How far

did you really think I’d go without you? Then—

Don’t you think that’s where you’ll find us now?