In 2014, my first semester as a graduate student at Columbia College Chicago, I took a mixed grad/undergrad class called Story and Performance with Bobby Biedrzycki. All stories we write are, in some way, about ourselves, but this was the first time I wrote stories that were explicitly about me and it was the first time I was asked to perform my stories for an actual, in-person audience. It was also the first time I stepped into a college classroom that asked me to take true ownership of my learning. I don’t know how to quantify the good it did me as a person, a teacher, and a writer.

(Side note: This was the last year, I believe, Story and Performance was offered as a grad/undergrad class in the creative writing department at CCC. It might have been the last semester that ANY grad/undergrad class was offered in the creative writing department at CCC. I have colleagues who took other grad/undergrad classes at CCC that semester and while their experiences were different, I couldn’t imagine taking this class without the enthusiasm, intelligence, and wide range of experience those undergrads brought to the table. Creative writing, especially in an academic space, likes to separate itself along lines of age and experience as a determination of quality, which I fear is both simply wrong about the nature of talent and detrimental to the growth of artists as a whole.)

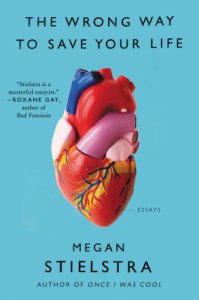

Megan Stielstra (author of Once I Was Cool and, most recently, The Wrong Way to Save Your Life) was often a guest in our class. Story and Performance had sometimes, in the past, been co-taught by Bobby and Megan. While Bobby was the only teacher listed on our syllabus, Megan was an important part of it’s narrative.

I had a hard time writing about myself. Fiction is invented narrative; when a detail conflicts with a narrative, it can be edited out or changed to support a theme or a plot. Fiction also has to make sense. If a character acts out of character, it’s (usually) bad storytelling.

People are also invented narratives, when you get down to the philosophical root of it, but instead of a clear narrative meant to please, disturb, or ultimately entertain an audience, people are a tangle of narratives. Pointless narratives. Dangerous narratives. Narratives that we embrace and narratives that we attempt to hide. They don’t often make sense. They change. They conflict.

When I was in high school, I had a messy friendship with a boy a few years older than me. I hadn’t spoken to him or about him in years, but I wanted to write about him. I wanted to write about all of him, all the weird and difficult parts of our relationship and how it had ended, but as I tried I found traces of him in more stories than I could anticipate. Of course I did. That’s how our lives work. You can’t just parcel out one person or one event and expect to find one story.

In the end, I wrote something okay but I didn’t stop thinking about all the ways that essay hadn’t felt right. Later in the semester, a conversation in class forever shifted my perspective. I wish I remembered the context of the conversation we’d been having or who had been speaking or what we had read, but it feels like we said it a hundred times over. That thing you’re trying to write about? You’re going to write about it again. You’ll see it differently – you’ll tell it differently – in a year, five years, ten years. It’ll be a part of a hundred stories, just passing through the background. It’ll come back in more ways than you could expect.

That’s what it feels like to read Megan Stielstra’s The Wrong Way to Save Your Life. Stories recur from one essay to the next in new and interesting ways, and we can see very clearly the way a life informs itself. Details of the apartment fire explored in “The Wrong Way to Save Your Life” (the collection’s title essay) appear as details in earlier essays. There’s a beautiful, heartbreaking essay about postpartum depression in Stielstra’s previous collection, Once I Was Cool, and there are (of course there are) more stories to tell about her experience. Each essay in The Wrong Way to Save Your Life is a masterfully intimate glimpse into a piece of Stielstra’s life and experience and she weaves these stories in a way that is both specific and universal. It’s a beautiful collection. If I could buy a copy for every person I know, I would.

Story and Performance, that class I took on a whim my first semester of graduate school, deeply changed my understanding of story and I am grateful to The Wrong Way to Save Your Life for reminding me of many of those lessons I let myself forget since I last sat in that classroom.

Share this: