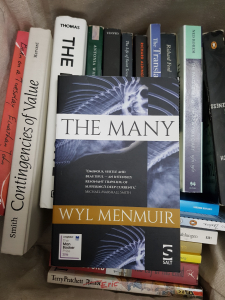

Menmuir, Wyl (2016), The Many, Salt

ISBN 978-1-784630485

So, to get things out of the way, this is a novel about grief, some of it quite affecting. Short books about grief are not uncommon. Max Porter’s debut novel(la) Grief is the Things with Feathers is an example of a well-executed book about grief and loss, as is Edward Hirsch’s Gabriel or Joan Didion’s memoir. The worst book I’ve read on the subject in past years was John W. Evans’s plodding and whiny Young Widower. Grief, whether autobiographical or not, is a powerful emotion for writers to mine, and I think it shows overwriting and overdetermination like few other genres. The stark simple fact of death and loss is so severe that it asks of the writer to be particularly mindful of the words and forms they are using, in contrast to writing about other strong emotions like love and desire, which can take a bit of overwriting, and in fact are sometimes enhanced by it. Max Porter’s examination of grief worked so well because he created a metaphor that carried much of the load for him; additionally, he used a language that was spare but not bland, with a fine sense of where to slip in and out of the events. Max Porter’s success was particularly interesting as he was one of the first of the recent wave of people from the “book industry” (Porter is a Granta Books editor) to come out with a fiction debut. Another one was literary agent Bill Clegg whose debut novel Did you ever have a family was longlisted for the 2015 Booker.

So, to get things out of the way, this is a novel about grief, some of it quite affecting. Short books about grief are not uncommon. Max Porter’s debut novel(la) Grief is the Things with Feathers is an example of a well-executed book about grief and loss, as is Edward Hirsch’s Gabriel or Joan Didion’s memoir. The worst book I’ve read on the subject in past years was John W. Evans’s plodding and whiny Young Widower. Grief, whether autobiographical or not, is a powerful emotion for writers to mine, and I think it shows overwriting and overdetermination like few other genres. The stark simple fact of death and loss is so severe that it asks of the writer to be particularly mindful of the words and forms they are using, in contrast to writing about other strong emotions like love and desire, which can take a bit of overwriting, and in fact are sometimes enhanced by it. Max Porter’s examination of grief worked so well because he created a metaphor that carried much of the load for him; additionally, he used a language that was spare but not bland, with a fine sense of where to slip in and out of the events. Max Porter’s success was particularly interesting as he was one of the first of the recent wave of people from the “book industry” (Porter is a Granta Books editor) to come out with a fiction debut. Another one was literary agent Bill Clegg whose debut novel Did you ever have a family was longlisted for the 2015 Booker.

Editor and consultant Wyl Menmuir added his name to that list with his own Booker-longlisted debut The Many. It is a solid book, written by a man with solid literary taste, a clever imagination and solid literary skills. Like Max Porter, Menmuir opted to write about grief, and like Porter, he uses an allegory to carry the reader through the story. But Menmuir is what I like to call a meddler – he writes the allegory in a way that requires him to “reveal” the mechanism behind it at the end, and he keeps dropping hints, in a prose that’s sometimes simple, and sometimes egregiously overwritten. Curiously, his set-up didn’t need him to use some of the tools of (magical) realism, and yet, in the first 3/4ths of the book, that’s what he does over and over – and these are not his strengths. In German, we say of mixed affairs like this that they are weder Fisch noch Fleisch, neither fish nor meat. And that’s what you get here – a good idea, a powerful emotion, and a writer who kept meddling in his own book, adding stuff here and there, resulting in a book that feels mostly like a missed opportunity. The idea could have made for a much stronger book, a truly affecting, moving, maybe even terrifying little novel. Instead we get a book that’s in between genres, in between styles, in between registers. If this book didn’t have the Booker sticker on the cover I wouldn’t have read it – to be honest, I might not have finished it. It’s a solid book, and quite short, so…maybe read it?

I’m not giving away the novel’s resolution here, and won’t describe how the allegory connects. But for 2/3rds of the book, it’s not really material how the allegory works – it’s true, you can go back and some curious passages work differently after you have more details on the allegory, than they did when you read them for the first time. At the same time, you’re always sort of aware that this is an allegorical set up, with various elements too staged, too portentous to work as realism, even magical realism. This makes the novel sometimes difficult to assess – a first reading is, after all, the most immediate, most important reading of the book. The book that came to mind as a comparison immediately was Graham Swift’s masterful novel Waterland. Now, Swift’s novel is so good that it is practically sui generis; I’ve not read another novel even by Swift that can compare with it. That said, it’s hard not to feel Menmuir draw from the same well in his set-up. The setting of The Many is a small fishing village dealing with a recent death. A young man named Perran has died. There is a general sense of gloom, and much of it feels immediately isolated and allegorical, but at the same time, Menmuir sets up a sense of place that could well be a real fishing village. He draws on the same sense of interconnection of history and nature that drives much of Waterland. We have a real sense of how this fishing village economy works, including an ominous representative of EU fisheries regulations. Into this village comes a man who is himself burdened with a recent loss. This man, Timothy, takes up residence in the house that was until recently occupied by Perran and is still full of his things. Again, we get a real sense of how objects interconnect with the life and history of the village and the many superstitions, habits and rules that are part of that life.

None of this is necessary for the allegory, mind you. If you step away from the text, you can see the allegorical bones of it, with the house, some of its furniture, the village and its inhabitants and a forbidding line of container ships that forms a taboo barrier for the fishermen. All the magical realism, all the Graham- Swiftness of the text is additional, it’s not needed by the text – you could argue that the damp atmosphere of the novel is important, but even it can do without most of these touches. What’s worst is that in order to make the book work despite all the additional weight, Menmuir pushes in a ton of flashbacks that keep us on our toes and sometimes focus us back on the overall structure. They are inserted awkwardly sometimes, but that’s not the main problem. The main problem is that Menmuir can’t leave a good thing alone. There’s the woman, maybe from the EU, who pays the fishermen for their catch of diseased dogfish. She stands on the docks, silent, with a grey coat. There’s a lot of weight in these descriptions, and a lot of power in the set-up, but Menmuir, in what feels like anxiety, keeps piling on, with sentences like “Her eyes impart something to him, something that suggests she understands, and feeling wells up in him, so much so he feels like he might be overwhelmed by it.” I’m not even here to judge the quality of that sentence as a piece of prose, but it makes very clear the author’s anxiety to really nail down all the meaning and foreboding he wants to nail down. Or, earlier: “He realizes then he is not fishing but hunting, and he watches for Timothy the way a hunter waits for a stalked deer.” The hunting metaphor is almost immediately discarded, and doesn’t add much to the text that the reader wouldn’t have seen themselves.

None of this is necessary for the allegory, mind you. If you step away from the text, you can see the allegorical bones of it, with the house, some of its furniture, the village and its inhabitants and a forbidding line of container ships that forms a taboo barrier for the fishermen. All the magical realism, all the Graham- Swiftness of the text is additional, it’s not needed by the text – you could argue that the damp atmosphere of the novel is important, but even it can do without most of these touches. What’s worst is that in order to make the book work despite all the additional weight, Menmuir pushes in a ton of flashbacks that keep us on our toes and sometimes focus us back on the overall structure. They are inserted awkwardly sometimes, but that’s not the main problem. The main problem is that Menmuir can’t leave a good thing alone. There’s the woman, maybe from the EU, who pays the fishermen for their catch of diseased dogfish. She stands on the docks, silent, with a grey coat. There’s a lot of weight in these descriptions, and a lot of power in the set-up, but Menmuir, in what feels like anxiety, keeps piling on, with sentences like “Her eyes impart something to him, something that suggests she understands, and feeling wells up in him, so much so he feels like he might be overwhelmed by it.” I’m not even here to judge the quality of that sentence as a piece of prose, but it makes very clear the author’s anxiety to really nail down all the meaning and foreboding he wants to nail down. Or, earlier: “He realizes then he is not fishing but hunting, and he watches for Timothy the way a hunter waits for a stalked deer.” The hunting metaphor is almost immediately discarded, and doesn’t add much to the text that the reader wouldn’t have seen themselves.

This overdetermination is a pity. I cannot say whether the novel, executed with a more focused sense of form, and with sentences that are sharper and clearer and more consistent, would indeed have been better. Looking at the simpler sentences, it’s not clear that this is a strength for Menmuir either, but anything would have been better than this hodgepodge. And there’s so many good ideas in here. There’s an early indication of an interesting comment on masculinity and communion, on intellectual work, on the meaning of family and communion, and some of the many, many dreams that swamp the book are very well done. But the most interesting part is the connection the author establishes between private and public grief. If Max Porter’s book is indebted to Ted Hughes, then Manmuir’s book surely owes a debt to Eliot. The village is indeed an “unreal city” and the title of the novel reminds us of that Dante line that Eliot incorporated into The Waste Land: “A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many.” There is an overwhelming urge in the book, particularly towards the end, to connect the private catastrophe with a broader public narrative. It is such an enormous sentiment, that it deserved a somewhat better novel built around it. An example of an excellent novel built around a coastal village, dealing with death and loss is A.L. Kennedy’s extraordinary story of young adulthood, aging and suicide, Everything You Need. I mean, as a reader, when I closed The Many, I almost felt a sense of loss myself: the loss of the good or even great book that this could have been. In my head I heard the lines from Donald Hall’s poem “Without” from the collection with the same name, mourning his late wife Jane Kenyon: “we lived in a small island stone nation / without color under gray clouds and wind / distant the unlimited ocean”

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the left and this link RIGHT HERE. If you liked this, tell me. If you hated it, even better. Send me comments, requests or suggestions either below or via email (cf. my About page) or to my twitter.)

Advertisements Share this: