Hi. Obviously I’m writing this much later than normal. Part of this is because I was in Tokyo from November 4th through the 12th, and the rest is due to jet lag/overall forgetfulness. I sort of wish I was posting pictures from my trip and raving about how much fun I had and how much I absolutely miss Japan with all my heart, yadda yadda, but here we are! It was my New Year’s resolution to do this every month of 2017 (kind of a weird thing to resolve to do in retrospect; also one that is increasingly irritating for me and probably even for you) and I’ve only got three more months of it, counting this one. So let’s get started.

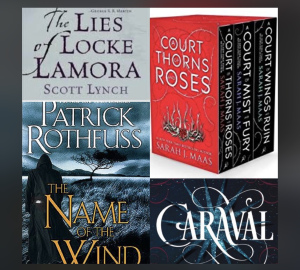

October reads, in chronological order:

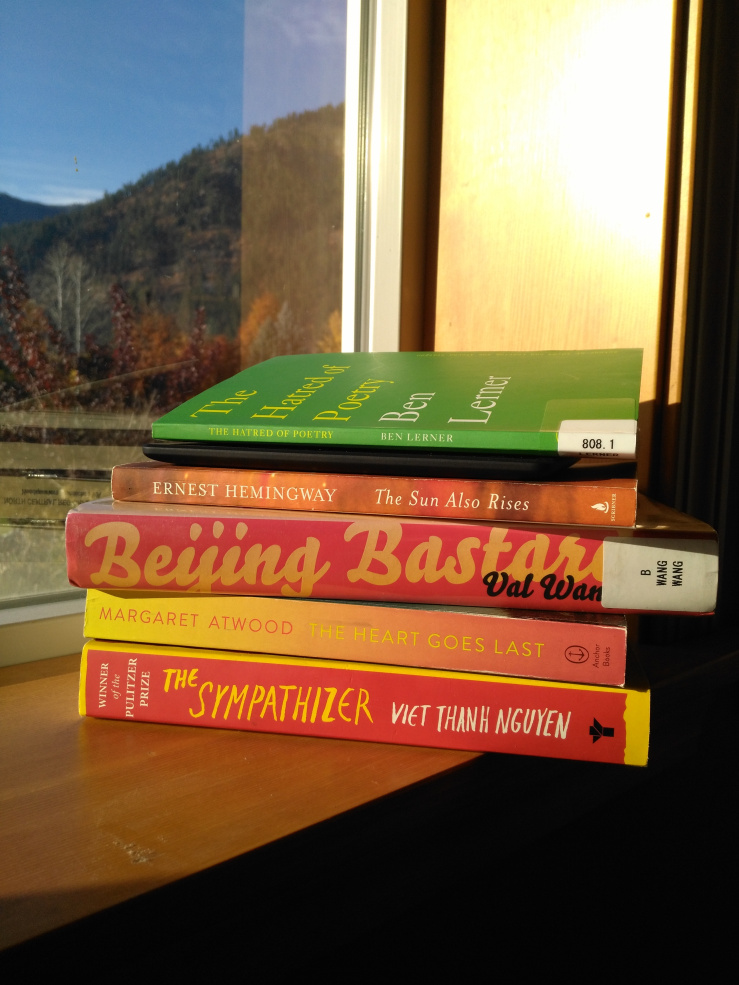

The Sympathizer | Viet Thanh Nguyen

Lately I’ve been reading a lot of East Asian literature, but nothing from Southeast Asia. I guess I don’t really know where to start. While Nguyen was born in Vietnam, he is Vietnamese-American, which probably helped make this book more accessible to someone like me who would like to read literature written from a Vietnamese perspective but can’t find anything like that at her local bookstore. Nguyen’s experience as Vietnamese-American arguably informs that of his protagonist’s life as a split identity. Our nameless narrator is the son of a Vietnamese woman and a white colonist, his father being present in his life as a religious figure in the community but never being anything resembling a father figure to his son. Because he is mixed race, the people of his community largely reject him as being “too white” to be truly Vietnamese. Eventually, he lands a scholarship to study in America, and as a result, returns with a near-perfect American accent and mastery of the English language. Not much later, he becomes a spy for the Vietcong during the war and flees with an enemy general and his family to America during the fall of Saigon. In America, however, he is too Vietnamese to be seen as American; the reverse of the issue he had at home. Nguyen follows this character’s life through his conflicting actions and motivations as a spy and what that means for his friendships, resulting in a complex and nuanced look at race, war, identity, and human relationships. In a way, it’s sort of reminiscent of Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night, which I read and reviewed earlier this year. There’s so much going on in this book and I barely scratched the surface here, but this has to be one of my favorite books I’ve read during this project. As a side note, even though he’ll never see this, special thanks to the clerk at the bookstore who saw me grab this book off the shelf and then went and found a cheaper used copy for me to buy instead.The Heart Goes Last | Margaret Atwood

Okay. I don’t like to do this, and maybe it’s because I haven’t really had to do this at all this year, but this was not a good book. I was given this book with the words “And by the way, you can keep it, I don’t really want, uh, need it back,” which should’ve been my first clue. I was expecting a lot after reading The Handmaid’s Tale last month and really enjoying it, but in comparison, this book felt like a million ideas crammed together, none of them ever being fully realized. It follows the lives of Stan and Charmaine, a young couple in a post-economic-catastrophe America, who are homeless and underemployed and longing for the life they once had. When offered the chance to live in a community called Consilience, gated and kept safe from roaming bandits, Charmaine jumps at the chance while Stan is a bit more hesitant. Even though the agreement to live in Consilience requires that residents spend alternating months living and working in the community’s prison, Positron, they sign on. The book sets itself up as a commentary on surveillance and Foucaultian ideas, but almost immediately drops off into a mess of chaotic plot points including sex robots, lobotomies, infidelity, investigative journalism, Elvis, and teddy bears. Every time you start feeling like you have a grip on the book, it thrusts you into something equally bizarre and underdeveloped. None of it feels intentional, or contributing towards some kind of post-modern conversation on narrative structure, which leaves a lot to be desired. Luckily, this was a quick read, and I was nearly racing at the end to free myself from its clutches.Beijing Bastard | Val Wang

This book was recommended to me earlier this year by a former professor of mine, and by chance I stumbled across it in the “book club” section of my library. It’s Val Wang’s memoir of her post-graduate decision to leave behind her NYC home and live in China, where her parents and their parents immigrated from. Inspired by the documentary film, Beijing Bastards, Wang’s ultimate goal in China is to film a documentary. About what, she doesn’t know yet. Along the way, she gets a job at a small newspaper as a journalist, improves her Chinese, learns her heroes aren’t all they’re cracked up to be, gets multiple terrible haircuts, joins a group of charismatic expats, and eventually ends up filming a documentary about the lives of a Peking Opera family hanging on to their antiquated art. It’s a funny book with a coming-of-age theme, that also gives the reader an interesting look into Beijing as it prepared for years for the 2008 Olympics, and a China much different than the one Wang’s parents had left behind.The Sun Also Rises | Ernest Hemingway

Can I be totally honest? English major aside, honest? I’ve never been wild about Hemingway. I read A Farewell to Arms on a flight from South Carolina to Washington when I was 18 and just never felt like picking up another Hemingway novel again. Maybe it was the fact that I was sitting in a middle seat next to two strangers, one of which was eating some kind of unappealingly pungent sandwich, but for a while I thought it was just because Hemingway and I never clicked. However, I needed a book to read this month and found this one that I bought at a library book sale sometime last year. I figured I wouldn’t have bought it if not for thinking I should probably give Hemingway another chance, a couple years outside of bratty teenage-dom. And honestly? I’m glad I did. Even though this novel is considered the quintessential novel of the Lost Generation, I found a lot of it to be relatable to anyone from my age group as well. It follows the lives of a group of young expats living in France as they travel to Spain for the bullfights (of course), and live their lives with the utmost cynicism, disillusionment, contempt, yet undeniable lust for life. Like everyone else who likes Hemingway, I enjoyed his prose style in the same way that I enjoy Robert Creeley’s concise poetic line: every word has a meaning and it speaks clearly and loudly and you’re super attuned to it. Basically: I really liked this book, and my Hemingway curse is gone, and I’d gladly read another work of his in the future, and I’m happy to no longer harbor this guilt and shame.The Art of Racing in the Rain | Garth Stein

Think back to your formative years and a book that really moved you at that time (don’t say Harry Potter, please don’t say Harry Potter. Please take this moment to prove to yourself and others that you have read other books besides Harry Potter). For me, that book is The Art of Racing in the Rain by Garth Stein. I loved it so much after I read it, I lied to my 10th grade English teacher and told him I’d never read it so I could do my final book report project on it (including turning in a journal full of reading notes taken on every chapter, necessitating a thorough re-reading). Well, I just recently actually charged my Kindle (don’t judge me on this; do judge me on how many parentheticals I use), and realized this book was on sale for $4 and thought to myself “Wouldn’t it be interesting to see if I still love it just as much now as I did back then?”. Make note of my mistake here and never do something so inconsiderate to one of your precious pleasant memories. Essentially, I was immediately underwhelmed by this book. I get that it’s written from the perspective of a dog, and thus it may make sense for the prose to be simple, but Natsume Soseki wrote three volumes from the perspective of a cat that are still hailed as some of the greatest works in world literature. Let me be totally clear, this is by no means a bad book. It’s heartwarming, it’s human (in a dog way), it’s heartwrenching but ultimately triumphant — it’s got everything most readers (whether they want to admit it or not) want to see in a novel. Albeit, the dialogue between the human characters is… not great to say the least. Corny at best. However, the fact of the matter is, something about this book really resonated with me when I first read it at 15, and that shouldn’t be overlooked. So, Harry Potter fans, I guess I owe you one, since your book actually holds up; but really, please read something else. Probably wasn’t my brightest idea to tarnish what was once a pure, fond memory of this novel, but what’s done cannot be undone (do you have to quote the really notable Shakespeare lines? Please help me stop inserting parentheticals).The Hatred of Poetry | Ben Lerner

I was recently recommended a book by Ben Lerner from a friend and for the life of me couldn’t find that book at any library in my area, but I did find this one. And I thought it was fitting judging by the title, because I too, as of right now and possibly the last 6+ months of my life, fucking hate poetry. Or maybe I hate the institutions surrounding poetry. Maybe, but I hate poetry too. Obviously, if you’ve read this blog at all pre-2017, you know it was almost exclusively an online portfolio for my poetry. And have you seen anything this year remotely resembling poetry I’ve written? Maybe one, I think? Okay, well have you seen me read any poetry during this year-long project of mine? Let me save you some time scrolling: nope, not a one. So then along comes this book, in which Ben Lerner in what I now believe to be his infinite wisdom discusses why people hate poetry so much, including those who write it. In a nutshell, he argues poetry and poems are not the same, that writing poems is so frustrating because they never capture the ethereal Thing the poet is trying to portray. Lerner makes an interesting point in stating that even people who don’t read any poetry at all can usually tell if they’re reading a bad poem, and why is that? Because in some way, we all know what poetry is not, even if we have no idea what it is. And while a good poem will never be the True Poem we’re all searching for, we should stop resenting the good poem and start realizing how what isn’t there brings us that much closer to what the True Poem actually is. I’m paraphrasing a lot, and using a ton of language he doesn’t actually ever use, and part of that is because I’m a fool and didn’t take notes on this book when I should’ve, but before I end this review I’ll add that if anything has brought me closer to reading and writing poetry again, it’s this little book. (Look at that! No parentheticals in that entire paragraph right there. What a champ. I deserve this one.) Advertisements Share this: