I’m indebted to Thomas More College literature professor Anthony Esolen for questioning why Sigrid Undset so seldom appears on lists of women offered as role models for girls aiming for greatness.

I’m indebted to Thomas More College literature professor Anthony Esolen for questioning why Sigrid Undset so seldom appears on lists of women offered as role models for girls aiming for greatness.

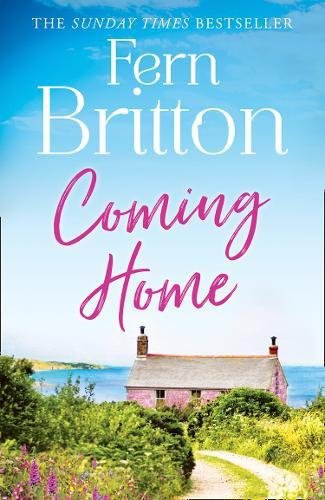

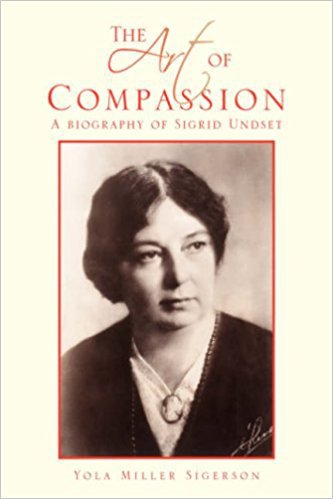

Reading The Art of Compassion: A Biography of Sigrid Undset by Yola Miller Sigerson, I now consider the oversight egregious. Undset’s response to the difficulties of life awakens a desire to become more fully alive, to be an independent thinker, a faithful Christian and generous lover with one’s art and life.

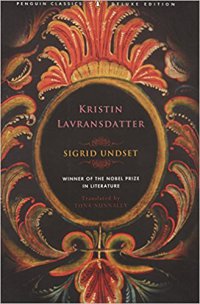

Kristin Lavransdatter, the medieval Norwegian trilogy for which Undset won the Nobel Prize in 1928, has recently been released in an Audible audiobook edition, and the moment has created fresh interest in the work of this remarkable woman. It is well deserved. Just a few facts from Undset’s fascinating life may help draw others to consider her merits and share them, especially with the young.

Undset is a profile in artistic perseverance and personal integrity. She actively supported the cause of women’s suffrage but maintained her right to independence from expected feminist tropes. Ever an articulate spokesman for causes she believed in, she knew what it was to be a lightning rod of controversy when it came to religion and politics. She produced novels both historical and modern as well as essays of apologetics, literary criticism and history, a biography of St. Catherine of Siena and much more during her very full life.

Undset was born in 1882 to atheist parents who raised her without religion. Her father, an accomplished and well-traveled Norwegian archeologist, died when she was eleven years old. Ever an independent thinker, the teenaged Undset found the one-sided approach to education at her progressive Norwegian school stifling. “It played an important role in shaping my character, inspiring me with an indelible distrust of enthusiasm for such beliefs,” she wrote in her autobiographical sketch for the Nobel Committee.

Undset was born in 1882 to atheist parents who raised her without religion. Her father, an accomplished and well-traveled Norwegian archeologist, died when she was eleven years old. Ever an independent thinker, the teenaged Undset found the one-sided approach to education at her progressive Norwegian school stifling. “It played an important role in shaping my character, inspiring me with an indelible distrust of enthusiasm for such beliefs,” she wrote in her autobiographical sketch for the Nobel Committee.

At sixteen, Undset left school to support the family income by working as a power company office clerk. She took up writing in her spare time and her first novel, completed when she was twenty-two, was rejected by a publisher who told her historical novels were “not her line.”

Undset kept on writing and her next two books established her reputation as a novelist. In her late twenties, she became romantically involved with a married artist, thirteen years her senior, who later married her after ending his first marriage. They had three children together, the second of whom was a mentally disabled girl who suffered debilitating seizures. In a time when many such children were institutionalized, Undset choose to raise her daughter Mosse in her own home. Mosse died at age 23.

When Undset learned that her husband’s first wife had abandoned his three children from that marriage to an orphanage, she took them in and somehow continued to write. Eventually her marriage dissolved and she continued to write, supporting her own children and at times her husband’s from his first marriage as well.

Undset was drawn to Catholicism while doing research for Kristin Lavransdatter, whose medieval characters are primarily Catholic though many are still tantalized by their homeland’s pagan roots. Five years before she was received into the Catholic Church, Undset’s third child was christened Hans Benedict Hugh (“Hugh” for the English convert Catholic priest and novelist Robert Hugh Benson). In a country in which Lutheranism is the state religion, her conversion was a very unpopular move, but Undset often used her writing gift to defend her faith against misunderstanding and libel.

Undset was drawn to Catholicism while doing research for Kristin Lavransdatter, whose medieval characters are primarily Catholic though many are still tantalized by their homeland’s pagan roots. Five years before she was received into the Catholic Church, Undset’s third child was christened Hans Benedict Hugh (“Hugh” for the English convert Catholic priest and novelist Robert Hugh Benson). In a country in which Lutheranism is the state religion, her conversion was a very unpopular move, but Undset often used her writing gift to defend her faith against misunderstanding and libel.

She had completed both the Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy and The Master of Hestviken when she received the Nobel Prize for Kristin. Undset gave the prize money away: fifteen thousand kroner to the Norwegian Authors’ Association and the rest divided between a fund supporting families who chose to raise their mentally handicapped children at home and another providing scholarships for families who wished to send their children to Catholic schools but couldn’t afford to do so. That last choice caused great outrage among her staunchly Lutheran compatriots.

In addition to her considerable writing achievements, Undset was fascinated with plant life and created beautiful botanical gardens on her property, bringing cuttings back from her travels and transplanting them with care. She owned rare books by taxonomist Carl Linnaeus that were salvaged from her home just before the Gestapo took it over when the Germans invaded Norway in 1940.

Undset’s life is inspiring to the end. Next: Return to the Future: Fascinating Facts about Sigrid Undset, Part 2, including Undset’s opposition to Hitler, her flight from her homeland, her years in America (including a secret assignment from Eleanor Roosevelt and friendship with Dorothy Day) and finally her return to postwar devastation in Norway.

More on Unset’s master trilogy: “Three Reasons to Make Time for Kristin Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter.”

Featured photo by Steinar Engeland on Unsplash

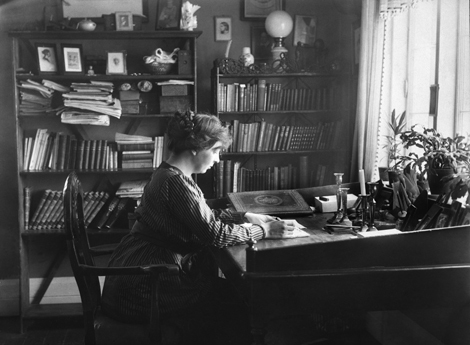

Photo of Undset at her desk by Avilde Torp – http://www.maihaugen.no/no/Bjerkebek/Sigrid-Undset/ Sigrid Undset – Maihaugen, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7454286

Follow Sparrowfare by placing your email address in the box in the sidebar. Inspire your inbox with regular posts!

Please share Sparrowfare

Save

Share this: