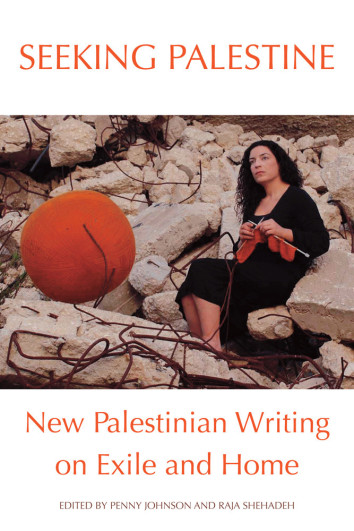

Penny Johnson, Raja Shehadeh, editors

Olive Branch Press

Your mother’s face once sustained you. Now you have to strain your memory to trace its outline. The place you were born in you can’t return to, even if it were so you could die there. Y ou can only be a nomad, an exile, or a refugee–never at home. Seeking Palestine, an anthology of nonfiction narratives gathers all these voices as it tries to make sense of the largely map-less Palestinian identity.

ou can only be a nomad, an exile, or a refugee–never at home. Seeking Palestine, an anthology of nonfiction narratives gathers all these voices as it tries to make sense of the largely map-less Palestinian identity.

Susan Abulhawa chases this elusive piece in “Memories in an Un-Palestinian Story, in a Can of Tuna”. In her personal essay, the author best known for her novel, ‘Mornings in Jenin’ captures the breadth of a Palestinian’s nomadic condemnation. Her words–funny and shocking and tragic–tell how she was ping-ponged across geographies as a young girl. Thus, despite growing up in the US for most of her life, she says, “…I have come to understand that it (my life) represents the most basic truth about what it means to be Palestinian–dispossessed, disinherited and exiled.”

“Exile” is the permanent address many have been left with since the Israel-Palestine conflict began with the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. And so as poet and translator Sharif L. Elmusa etches in an essay combining his poetry and prose with river-like flow, not only their presence but even the absences of Palestinians are portable. To lug this presence/absence around, a Palestinian pays steep baggage fees. “I can only go inside myself / into the maze of the hippocampus / which is like going inside a pyramid / and finding the robbers had carted away / the belongings.// What will I shed this round / to complete my portable absence?”

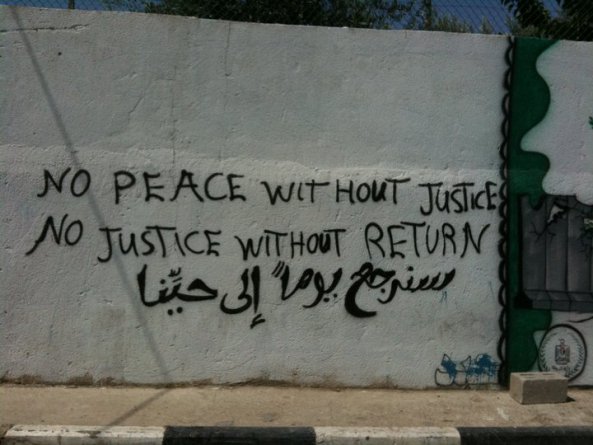

In Elmusa’s unresolved puzzle lies a fundamental kernel of the Palestinian struggle — resistance. To resist isn’t a political act but a pact one must make early on in life — for survival itself. Especially when one’s existence is shaped in refugee camps, bombed schools and hospitals, occupied territories and dreaded checkpoints.

It is a sort of resistance that brought back Lila Abu-Lughod’s father back to Palestine after living in the US for forty years as an exile. Abu-Lughod senior was a scholar and professor of political science in some of the most reputed North American universities. A medical condition impelled him to return to his homeland; he felt his time was running out. In “Pushing at the Door,” Lila tracks not only that journey — its irony and pathos — but its inter-generational roots, leading back to her grandmother and her dislike of the neighbourhood she found herself in after her family fled their home (she didn’t want to leave) in the early days of the fighting. Her problems, seemingly simple — the absence of a public bakery and having to buy bread — point to the many compromises a refugee must make to survive. What is perhaps the most telling in this lovingly-profiled essay is a recurring nightmare Abu-Lughod’s father had been suffering from since 1948 — a nightmare that is the Palestinian tragedy.

The dream never changes…I am living by the sea–the house I grew up in was in Jaffa, right by the sea. A thief comes, a burglar. He starts pushing open the door and I try to shut it. A struggle that doesn’t end. He pushes and I try to shut the door…And I scream but no one hears me. I’m shouting to the people in the house that someone’s breaking in, but no one hears.

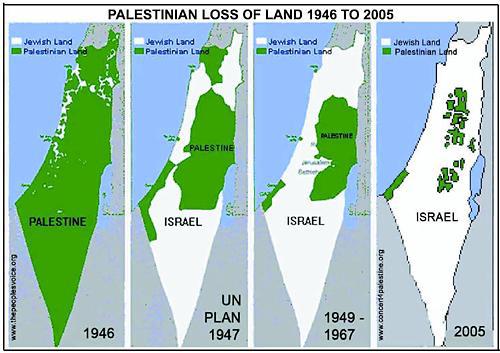

That the nightmare is a continuing one can’t be lost on the reader. Israel continues to build more and more settlements in Palestinian territories and despite decades of struggle, the voices of the people displaced from what was originally their land seems to fall on deaf ears within the international community.

In “Onions and Diamonds,” Mischa Hiller, an English writer of Palestinian origin looks at the theme of exile with a refreshingly liberating view. He recalls Edward Said’s memoir “Out of Place” to make the point that exile need not always be a dirty word. He cites the examples of self-exiled American writers, Jewish writers forced to flee during the Second World War and contemporary Arab writers in exile. Returning to Palestine isn’t just about the right to reclaim a physical space (irreversibly altered by Israel) but having the freedom to “graduate from being dispossessed to becoming an exile,” for him.

Israel’s occupation of Palestine doesn’t stop at territorial boundaries. In “Of Place, Time, and Language,” Adania Shibli writes about the intellectual occupation of young Palestinian minds that starts as early as their school years. The curriculum taught in Palestinian schools is subject to the approval of the Israeli Censorship Bureau, which allows teaching texts from different Arab countries except Palestine. What if those stories got the children thinking about the Palestine issue? Another thing makes Shibli’s essay interesting. She writes how every time she enters Palestine, her wrist watch stops working. Once she leaves the place, the watch works fine. Like Abu-Lughod’s nightmare, this, too, is a metaphor for Palestine itself — a place where time has stopped and refuses to move, regardless of all the strides elsewhere in the world.

No other piece in the book captures the violent and browbeating takeover of Palestinian territory, and along with that, its people’s society and culture like Rema Hammami’s “Home and Exile in East Jerusalem.” Hammami chronicles with humour and journalistic ardor, how within a decade (1992-2002), the neighbourhood where she lives in Nablus went on from being a gentrified Palestinian locality to a place devoured by Israeli settlements; how people’s houses are overtaken by the state of Israel and even while the matter was in court for settlement, guards were posted in a Palestinian’s property. And about how people construct their dehumanized lives in the face of continued bombings, airstrikes, and flagrant human rights abuses.

As with many others in the city…the main ingredients of my life were on the other side–in the theatre of war. My commute to work now involved crossing four of them (checkpoints) each way–each with its own random moods, ludicrous demands, and particular expertise in sadism.

One of the most powerful voices in Seeking Palestine is that of Jean Said Makdisi’s. Writer and researcher Makdisi is also the sister of Palestine’s best-loved intellectual, Edward Said. Her essay “Becoming Palestinian” draws upon family history and her father’s influence in creating for Jean and his brother a deep sense of connection with Palestine and its history. More importantly, though, Makdisi makes a crucial point in the context of the Arab-Israeli conflict–the role of Palestinian Christians. She points out how the propaganda of the conflict tries to portray “the Judeo-Christian Western world in an endless conflict with the Muslim world over the ‘Holy Places’ in the ‘Holy Land’.” Restoring Christian Palestinians to their legitimate place in the public awareness is key to dismantling this idea of a religious clash, Makdisi feels.

An anthology of narrative nonfiction on Palestine that’s not academic in nature runs the risk of succumbing to cliched tropes of nostalgia and sentimentality. Editors Penny Johnson and Raja Shehadeh must be commended for making this an anthology which, despite drawing heavily from memory relies on straight facts, deep humanity, and lucid analyses, not maudlin reminiscing.

Shortly before writing this, I posted a question for my friends on a social media platform. What did home mean for them, I asked. The responses were varied but the common patterns alluded to comfort, security, acceptance, and freedom. And returning. The last pattern is a crucial absence, even an impossibility, for many Palestinians. When you can’t return home, the least–or the most, depending on how you view the situation–you can do is to seek your home. Like tracing the outline of your mother’s face in your mind because you can no longer see her.

Hence, Seeking Palestine.

Advertisements Share this: