June 1, 2017

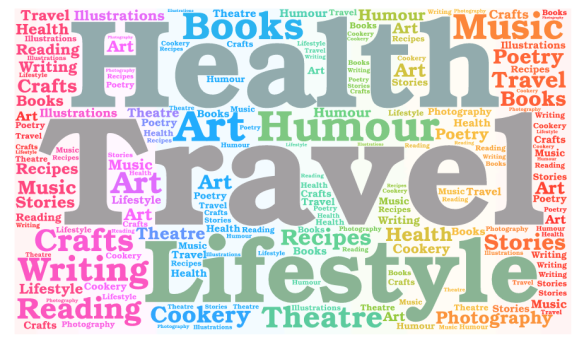

I recently read a book called Some Kind of Happiness by Claire Legrand. The short synopsis is this: 11-year-old Finley Hart deals with anxiety and depression – without knowing they carry those names. To escape from it, she writes about this fantastical forest called the Everwood. When she’s sent to live with her grandparents for the summer, she goes on a magical journey that brings her face to face with her anxiety and depression. It’s a phenomenal read, and I blew through it in just under five hours because I was attached to this character from the very first page.

I think the reason I was so attached to her is because I have never related to a character more than I have to Finley. Her brain works the same way mine does. Though our situations are very different, we cope the same way – writing.

Finley has what she calls ‘Blue Days’. On her Blue Days, her brain is freaking out in every way possible. She feels helpless, sad, has panic attacks, can’t think straight, argues with herself constantly, and she doesn’t want to get out of bed. She doesn’t like to talk about these days because part of her doesn’t believe she should be feeling sad and anxious, and the other part of her thinks that no one will understand what she’s feeling. Throughout this whole novel, I wanted to reach out to Finley and say, “Girl, I know what you mean. I know what you’re feeling. You’re not alone.”

My Blue Days usually show up every month at different times throughout. At the end of the month, I usually look back to see that they take up an average of about a week. They’re days that I tend to block out after the fact, and try to convince myself that what I was feeling wasn’t important or valid. The earliest I remember having Blue Days is sixth grade. Since then, they’ve been ever-present, and I’ve learned to deal with them very internally – not telling anyone, but telling myself they don’t actually exist. It wasn’t until I read this book that I felt somewhat comfortable with them and decided to acknowledge them with a name.

I really loved how the author chose to call Finley’s bad days ‘Blue Days’. It gives them more meaning. These days should have meaning, because even though it’s not a good day, it’s a day that you’re alive. It’s a day that you have fought through and came out on the other side. It’s hard to see anything at all when a Blue Day is occurring, and in the rear view mirror, they usually look like wasted days. The thing here is that they’re not wasted. Each day – whether it’s fantastic or awful – gives you more information to better understand yourself. That’s what I get out of both types of days: when your brain is happy, when your brain is sad are all times that allow you to look over yourself and see what’s going on. I don’t know what exactly causes my Blue Days or what causes the opposite of them, but I, for the most part, have learned how to handle myself on both types of days. The more you understand yourself, the better you can help yourself. Your intentions have to be in the right place, but even then it takes a while to get where you need to be.

At the beginning of this year, I wrote a blog post about my word of the year: intentional. I think I’ve been doing okay with it this year. It’s baby steps, like noticing when I should’ve said ‘bless you’ to someone or when I should’ve said ‘hello’ to my boss at work before she said it to me. It’s baby steps, like understanding that this is a new concept, and I have to rewire my brain in order to fully give myself to this concept of being intentional. It’s baby steps, like realizing that Blue Days don’t define you, and that your feelings are all valid, no matter what they are.

There are so many fantastic quotes in Some Kind of Happiness. I marked so many of them in the book, but I’ll leave you with one that I think it so important in our journey to understanding our sad and anxious brains:

“If I am a puzzle, this is the moment in which I find the first corner piece. There is still a lot of work to do; I still have a thousand pieces of myself to fit into place. But everyone knows you’re supposed to find the corners first. They are the beginning.”