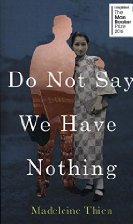

Madeleine Thien, Do Not Say We Have Nothing (Granta 2016)

Before the meeting: This book tells a story of three generations of a Chinese family in the 20th century. It includes a graphic evocation of the horrors of the Cultural Revolution and the purge of ‘Rightists’ that preceded it, and an equally graphic account of the events surrounding Tiananmen Square in 1989, as gleaned by a young woman of the Chinese diaspora who was born and brought up in Canada.

I found the first 50 pages hard going, as the different time periods were introduced, with no clear indication of how they were related. But once the several stories were up and running, I was engrossed.

Of the vast amount that has been written about this period in China, I’ve read Han Suyin’s Wind in the Tower, in which the Cultural Revolution is seen as a brilliant strategy to save the revolution from living death, and William Hinton’s Fanshen (1966) and Shenfan (1984), brilliant accounts of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural revolution as they played out in a single village (I saw David Hare’s play of the former at the Pram Factory in Melbourne and then at Belvoir in Sydney). I haven’t read any of the famous memoirs such as Li Cunxin’s Mao’s Last Dancer and Jung Chang’s Wild Swans, so I can’t say how this novel compares to them, but I can say that it makes Han Suyin look like a PR spin merchant, and gets horrifyingly deep under the skin of the kind of events William Hinton describes.

It doesn’t come across as anti Communist propaganda; it’s more a terrible tale of a dream betrayed. Even as people’s lives are being destroyed they stay firm in their belief in the revolution. Partly this is a survival mechanism – if you can say the correct slogans with sincerity your chances are greatly improved. Partly, though, it’s also a result of the power of the Maoist dream. The shattering of that dream as the People’s Army turns on the people in 1989 is among the most heartbreaking writing I’ve ever read.

Like any powerful novel, this one doesn’t let the reader imagine that the events it portrays are safely of another time and place. Call-out culture on the internet these days may not be as savage as the criticism sessions in the Cultural Revolution, but it shares some of its structure of feeling. The power of slogans to block complexity is having devastating effects on lives in Australia – or more precisely offshore from Australia – as I write this. The term ‘climate change’ is being expunged from Donald Trump’s US agencies as surely as ‘counter-revolutionary’ knowledge was erased under Mao. [Added next day: not to mention ‘fire and fury and – frankly – power’.]

I cried a lot.

After the meeting: The conversation stayed with the book for most of the evening, and even when it departed it was still tangentially related.

Not everyone loved the book as much as I did, but I came away from the evening with an enriched appreciation for its complexity. I think it’s true to say that everyone had at least one scene or character that had struck them. A couple of us said we found the descriptions of music didn’t work; someone said that these descriptions were clearly important to the characters, but not really to the reader. One chap said he had got out his recording of Glen Gould playing the Goldberg Variations – the same recording as features in the narrative – and put it on it while he read, and that this had worked brilliantly.

So not only is this a terrific novel to read, but judging by our experience it’s also a terrific book club title.

Share this: