1 MEMOIR

Ann Lamott wrote that “you own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.” Below I’ve picked three memoirs that I’ve enjoyed over the past month and will follow with my pick of fiction and non-fiction over the next week.

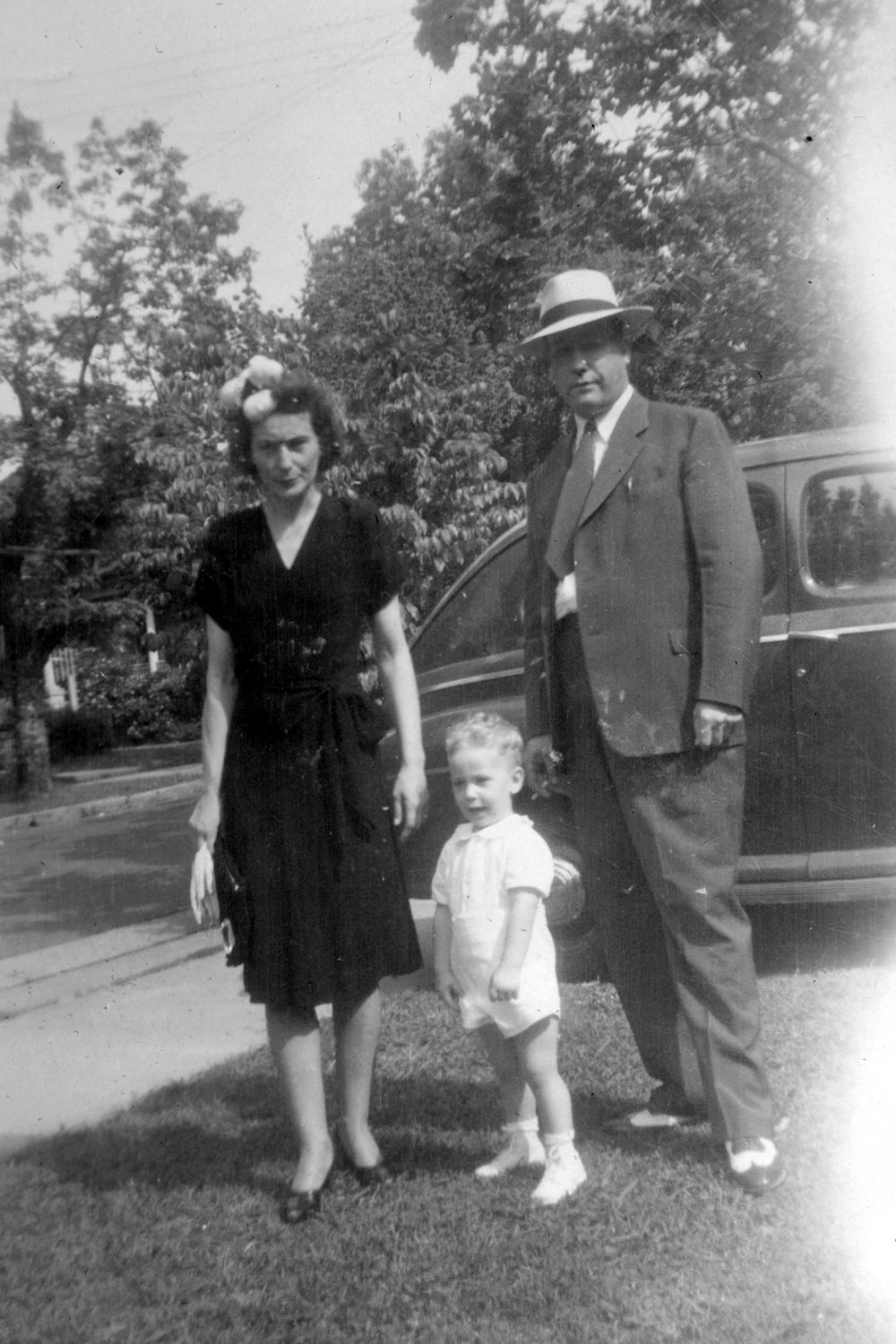

Between Them: Remembering My Parents by Richard Ford ( Bloomsbury)

For any Ford fan this is a must read as the Pulitzer Prize winner writes with affection and some humour about his parents Parker Ford and Edna Akin. The memoir was originally written as two essays written decades apart and in their fusion creates one of the most extraordinary depictions of loss in literature. Ford writes first about his father, Parker, a traveling salesman who died in Ford’s arms in 1960 when Ford was 16. He wrote the piece about Edna, his feisty, independent mother shortly after her death in 1981. In the author’s note at the beginning of the memoir Ford acknowledges that writing the two memoirs thirty years apart he has permitted some inconsistencies persist between the two timelines and has allowed himself the lenience to retell certain events.This is a subtle and beautiful testament to devotion and a writer repaying parental love with his exacting prose and ability to animate his parent’s lives. In the afterword to the memoir Ford writes that ” the fact that lives and deaths often go unnoticed has specifically inspired this small book about my parents and set its task” and that ” the chore for the memoir writer is to compose a shape and an economy that gives faithful, reliable, if sometimes drastic, coherence to the many unequal things any life contains.”I had the privilege to hear Richard Ford read from this memoir at Listowel Writer’s Week last month, his voice suffused with emotion and deep south charm inducing a trance like state in the audience where we confronted some of life’s beautiful but painful truths.

Once We Were Sisters by Sheila Kohler published by Canongate.

South African novelist Sheila Kohler has been haunted by the death of her sister, Maxine, who died a violent death on a spring night at the hands of her abusive husband. This memoir is the author’s attempt to unravel the truth of what happened and sift through the sands of memory to recapture the privilege of their childhood in 1950’s South Africa, a society where colonial gentility co-existed with violence and privilege. This searing illumination of sisterhood starts in 1979 when Kohler hears the news that her brother-in-law, a protege of heart surgeon Christian Barnard, drove off a deserted road and into a lamp-post causing the death of his wife Maxine. When Kohler sees her sister’s face in the morgue she feels guilty about not saving her from a husband they knew to be unspeakably cruel. She soul searches through this memoir and confronts the dark questions that her sister’s death bring to the surface including her own passivity which may have been exacerbated by the misogyny of 1950’s South Africa. This memoir is written in the present tense which reminds us that Kohler’s sister is forever with us and in her stark and delicate prose she captures the sensuous South African childhood of “swimming in the big pool, picking armfuls of bright flowers, gathering oranges and lemons” as well as the heart of darkness that destroyed this paradise.

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy

This memoir by New Yorker writer Ariel Levy confronts the notion of having it all. She was riding high in 2012, successful at her chosen career, legally married to a woman and pregnant with her first child. ” Thanksgiving in Mongolia” is the heart -breaking essay that Levy wrote about the miscarriage that happened in a hotel room in Mongolia where she had flown to do a report on the country’s mining boom.Her memoir picks up where the essay leaves off and explores the aftermath of the miscarriage where her marriage fell apart and Levy felt that the Universe had delivered her a karmic blow for dreaming that she could live a life of her choosing. Of her generation, Ms. Levy writes: ” Sometimes our parents were dazzled by the sense of possibility they’s bestowed on us. Other times, they were aghast to recognise their own entitlement, staring back at them magnified in the mirror of their offspring.” This memoir confronts taboos and life-shattering events in self-lacerating detail and ends with a Austenesque happy ending though in typical Levy style she has declared that this is not an ending as she is not dead.

Advertisements Share this: