One of the coolest things about living in Portland now is the fact that Multnomah County has an extensive library system. Since Rachael and I are still in the middle of trying to get our stuff from our move (most recent update: it’s been found but needs to be shipped to us), my personal comics library is currently in limbo, leaving me to depend on the much more extensive public library to acquire reading material in these waning weeks of summer.

I may have gone a little overboard when we first arrived in town, putting holds on fifteen comics titles over the course of our first weekend with no idea how long it would take for them to become available at my local branch for pickup and consumption. The intervening week between us learning that our stuff was missing and Uhaul letting us know they’d found it saw me growing increasingly dismayed as I received notices that three or four books would suddenly be available for pickup at a time. Fortunately, we live less than half a mile from the local library branch, so this has been a good excuse to take the occasional walk around the neighborhood. Unfortunately, I now have about ten titles sitting on a shelf in our apartment that I need to read through in less than three weeks. That’s not undoable, but it does mean I’m not doing as much savoring with comics that I really enjoy (case in point: I read the second volume of Lumberjanes the other day and found it incredibly delightful, but went ahead and returned it after anticipating a lack of space and time to fully reflect on it).

I have read a few things that I think are worth spending a little more time on. The first book that I picked up from my reading binge is P. Craig Russell’s adaptation of Richard Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung opera cycle. It caught my eye because I recognize Russell’s work from the couple of stories he collaborated with Neil Gaiman on for The Sandman (specifically issue #50 “Ramadan” and the Death story from Gaiman’s Endless Nights comic anthology), and Wagner’s opera cycle is one of those Western cultural touchstones that echoes broadly in the popular imagination but suffers from feeling esoteric and inaccessible to folks who don’t already enjoy opera (and also don’t speak German). Russell’s adaptation was appealing because it purports to be a relatively faithful translation of the operas’ librettos into English paired with the rhythm of comics storytelling as a substitute for staging and musical performance.

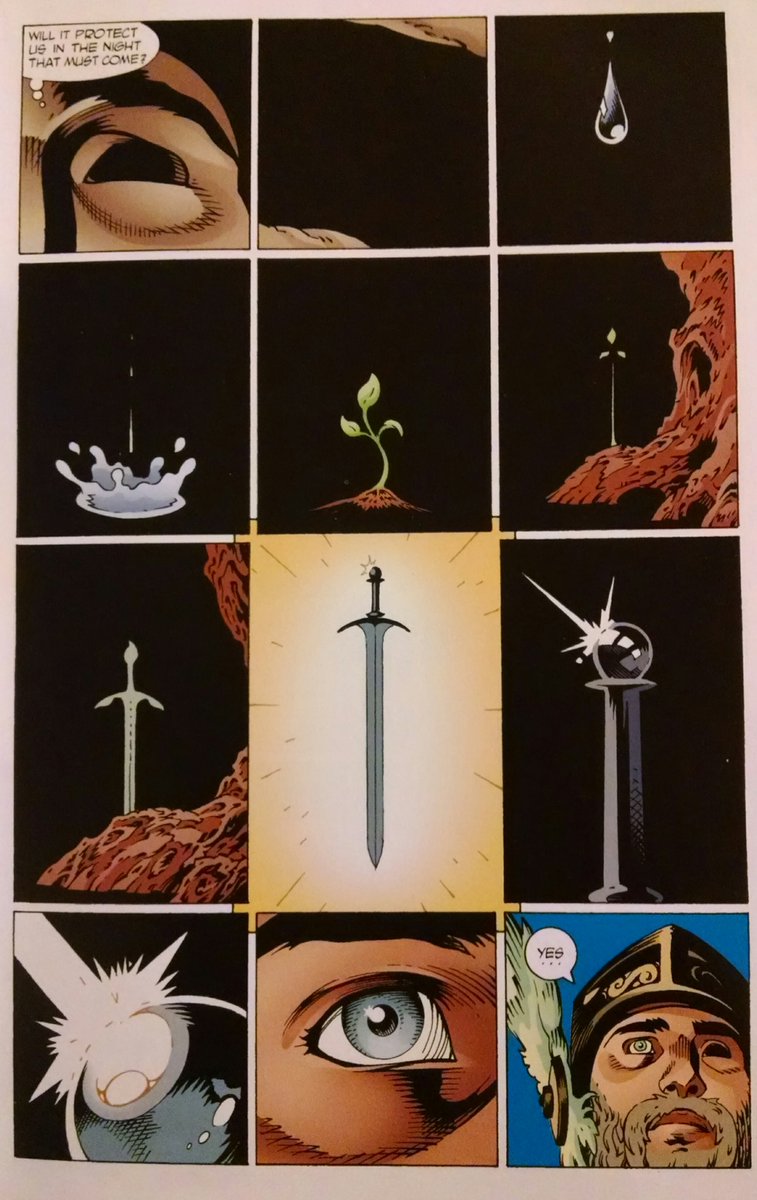

The drop of liquid, sprout, and sword are recurring visual motifs that stand in for leitmotifs that exist in the original operas. (Art by P. Craig Russell, colors by Lovern Kindzierski, letters by Galen Showman)

The entire work is quite sizable for a graphic novel; each individual opera in Wagner’s cycle is adapted into its own three- to four-issue story. All in one volume, that means there are approximately fifteen issues to read, and with the more stylized language of the text, that means this is something that takes a little bit of time to read (I think I spent about six hours reading the whole thing). Russell’s art is lovely throughout, and he demonstrates a strong aptitude for conveying abstract ideas through visual interpretation of the action; Wagner’s work is famous for its intricate use of leitmotif to clue the audience into the emotional beats of the story he’s telling, and Russell takes those musical cues and translates them into repeated images and visual patterns so that someone like me, who has never listened to any of the Ring cycle beyond its most famous pieces, can pick up on those ideas without having any familiarity with the music that it’s adapting.

Setting aside the craft of the adaptation, there’s a lot to unpack in Wagner’s retelling of old Norse (via Germany) myth. The cast of characters revolves around Voton (Odin) and his extended family as they experience various struggles set up by the curse set on the eponymous Ring of the Nibelung. The Ring’s origin is the subject of the first story, The Rhinegold, where a dwarf from Nibelheim (a Nibelung) named Alberich plots to steal a gold nugget nestled at the bottom of the Rhine river that shines like the sun. The Rhinegold is protected by spirits of the river who caution Alberich that anyone who takes the gold and forges it into a ring will have dominion over the world, but at the cost of never experiencing love. Alberich, frustrated by the teasing and taunting of the spirits accepts this price and steals the Rhinegold away, deciding that he’s already unlovable as an ugly dwarf. Meanwhile, Voton is busy trying to worm his way out of a deal with the giant brothers Fafnir and Fasolt where he promised them Freia, his sister-in-law, as payment for construction of Valhalla. These two plotlines intersect when Voton, on the advice of Loge (Loki), decides to steal the treasure of the Nibelungs, amassed under Alberich’s rule, and the Ring as a way of consolidating his own power over the world and to provide an alternative payment to the giants. Things go south, as one might expect, and once Voton and Loge trick Alberich out of possession of the Ring, Alberich curses it to always be an object of envy and to bring death to any person who possesses it. From there, things just get generally worse.

Brunhilde is easily the best character if only because she sees through all of Voton’s crap. Unfortunately, most of her character arc is an exercise in humiliation in service of Voton’s larger plan. (Art by P. Craig Russell, colors by Lovern Kindzierski, letters by Galen Showman)

Thematically, a lot of the Ring cycle has to do with Voton’s attempts to circumvent fate and hold on to his power as the All Father. It’s all about the inevitability of decline and replacement with newer powers; the pure love of Brunhilde and Siegfried is both the catalyst for the gods’ ultimate downfall and the thing that serves as the new, central force of the recreated world. It’s essentially a thing that Voton can’t control for himself, and it’s that one quality that allows it to endure where all of his other plans ultimately fail (perhaps the most interesting dilemma of the whole cycle to me is the way that Brunhilde, who is ostensibly an extension of Voton’s will as his daughter by Erda, mother of the Norns, asserts her own will while trying to carry out Voton’s wishes. Generally speaking, Wagner is cruel to his female characters and often paints them in typically sexist ways, but Brunhilde at least gets this one moment of depth. She’s both fated to do what Voton commands, enforcing the Ring’s curse, and the key to breaking his plans so that the world can begin anew. For all the other obnoxious things that Brunhilde has to suffer (not least of which is the fact that Voton dooms her to be subject to whatever man comes along and finds her on her mountaintop), her decision to defy Voton’s explicit commands enjoys a pivotal position in the cycle’s overall narrative.

Though I don’t know that Russell’s adaptation of The Ring of the Nibelung is something that I’d be inclined to re-read in the future, I think it is a remarkably accessible way to get an introduction to Wagner’s work. Now that I’ve read a version of the story in English, I feel more inclined to explore the operas, although that may just be a pipe dream.

Advertisements Share this: