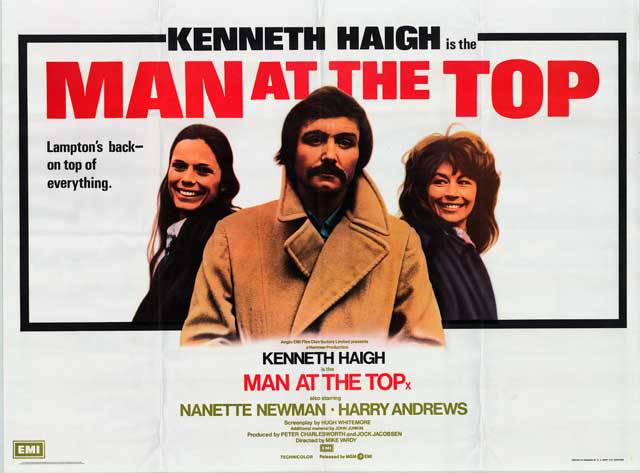

Man at the Top came along at the end of Hammer’s classic era, in 1973, when the company was struggling to finance anything and had gone full circle, returning to their roots in adapting TV series – mostly sitcoms, but also dramas like this – into feature films. This film has a more confused heritage though, given that the original series was itself a sequel to the classic 1959 ‘angry young man’ films Room at the Top and its 1965 sequel Life at the Top – so in a sense, the film is the third film in the series, though perhaps unofficially (writer John Braine is not involved here, although he did write the TV series).

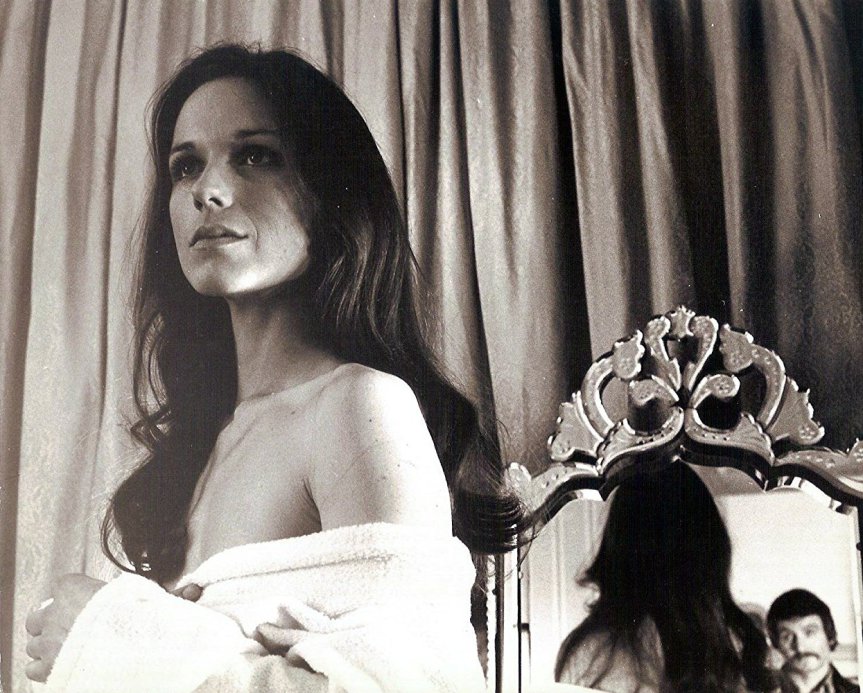

The movie is a rather muddled combination of class war drama and thriller, as Joe Lampton (Kenneth Haigh) – no longer young, and less angry than cynical – has achieved the success he’s looking for and is now enjoying the fruits of his wealth. Taking a job as an executive at Lord Clive Ackerman’s (Harry Andrews) pharmaceutical company, all seems good – especially as he quickly beds his employers trophy wife Alex (Nanette Newman). But the suicide of his predecessor sees him digging deeper into the new ‘wonder drug’ that the company are using in Africa and he soon discovers that all is not well – early versions of the drug left women sterile, and the company are simultaneously covering it up while setting Joe up to be the fall guy should the truth come out.

The film, while not what you would call gritty, certainly reflects the early 1970s British cinematic style, where everything is grey and everyone is a bastard. As Lampton tries to uncover the truth behind the cover-up, you are aware that he’s doing this out of a sense of self-preservation rather than to expose the truth, and is more likely to use the information to his own advantage than for the public good. His clashes with upper-crust Andrews are replete with class war tensions, but in fact seem as much about personality as background – Lampton has no respect for the airs and graces of Ackerman and his clan, while the toff despises everything Lampton represents. As more than one character comments, Lampton is “a shit”, and it’s hard to disagree. But as the film suggests, you have to be a shit to thrive in the world that he lives in, and Lampton will do whatever it takes to be the biggest shit of them all.

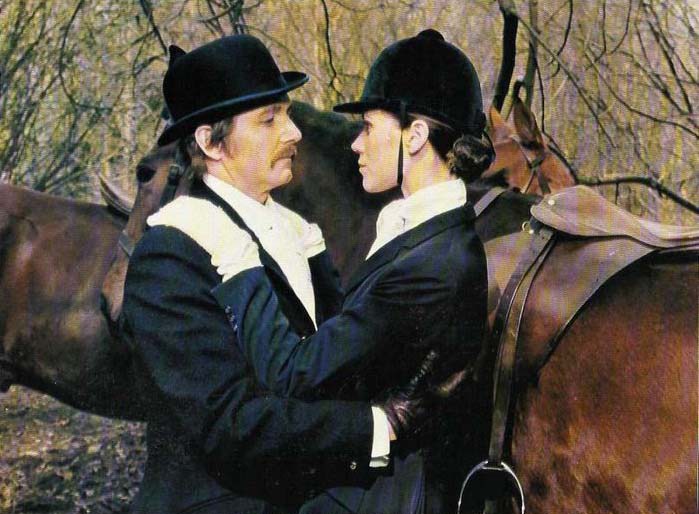

There are moments where the film takes on the feel of Get Carter or the first Sweeney film, thanks in no small part to a typically understated and groovy Roy Budd score, but this isn’t a crime drama so much as a drama with crime in it. When Lampton threatens to expose Ackerman, there is a tense fox hunt (with Joe as the fox) that is as impressive as any British crime thriller of the era, but really, this is about the lust for power, and all that it brings. The film’s sex scenes – notable for the surprisingly frank nudity from more or less all the female cast (though Newman is clearly replaced by a body double) – are all power plays: the bedding of Alex, the seduction of/by Ackerman’s daughter (Mary Maude) that turns out to be something of a honeytrap and even Joe’s brief dalliance with a couple of hitchhikers (Angela Bruce and Margaret Heald), where post-hippy drop out ideals are rubbished by Lampton, who – accurately – points out that today’s teenage revolutionaries will be tomorrows bankers and office workers.

There are some unusual names popping up in the cast. Boxer John Conteh appears early on as ‘black boxer’ – but before you think that’s classic 70s racism, there’s also a character called ‘white boxer’. In fact, the film is remarkably progressive for the era, as comedian Charlie Williams pops up (giving an unexpectedly decent performance) as a Northern comic married to a white woman and the father of Angela Bruce. The fact that the mixed-race marriage is neither shown as unusual or commented on by anyone in the film is pretty unusual for the era, when even liberal filmmakers might’ve put in a double-take or two.

The film ends as cynically as you might expect – Joe Lampton is, after all, a shit. If there is a class war at the heart of the story, then he’s the winner, but at what cost remains to be seen. It ensures that the film doesn’t end in the way you might want, but in the way it had to.

While not quite a lost classic – and certainly not as significant as the film that launched Joe Lampton into the world – Man at the Top is a fascinating, always completely watchable drama, and certainly deserves better than being the almost forgotten film that it currently is.

DAVID FLINT

BUY IT NOW (UK)

Advertisements Share this: