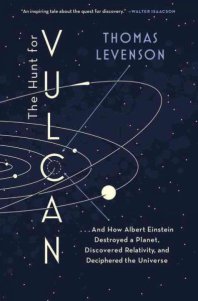

Outside of a few biology topics that related to animals, I was never much interested in science during my high school years. So I’m making more of an effort, as an adult, to expose myself to science topics. First, because it’s good to learn new things: it makes the world make more sense (and you’ll probably be wrong less often, which is always nice). Second, because science literacy in the U.S. is generally terrible and I want to at least try not to be part of the problem. The Hunt for Vulcan caught my eye last year (at R. J. Julia in Madison, CT, which is an awesome store) because it sits at the intersection of science and history. Since I was already interested in history, I figured this would be a good one to start with.

First, the story behind the title. Vulcan isn’t a reference to Star Trek, but the name of a hypothetical planet that, in the mid-to-late 19th century, was thought to lie between Mercury and the sun. Why did anyone even come up with that idea? Because there were slight irregularities in the orbit of Mercury which could not be explained by Newtonian physics. And rather than call Newton into question, when all other observations other than Mercury agreed perfectly with his theories, it was proposed that an unknown planet was affecting Mercury’s orbit.

As it turns out, The Hunt for Vulcan is really more of a study of the scientific method in action than a history of the Vulcan theory. Specifically, it’s a commentary on how the scientific method is not nearly as clean and neat in reality as it is on paper. In theory, scientists are supposed to discard a hypothesis when it doesn’t match observations. In practice, of course, human biases get in the way, and ideas linger. Intuition also plays a larger role in scientific advances than is commonly thought. Levenson explores all this through a history of Vulcan “sightings” – which turned out to be nothing more than people seeing what they wanted to see, or already expected to be there – and a detailed history of Einstein’s thought process as he formulated special and general relativity (which finally put the last nail in Vulcan’s coffin).

One point I especially like that Levenson makes clear, is that Vulcan was actually a sensible idea given the state of science at the time. It really wouldn’t have made sense to scrap Newton when everything else was working so well. Some great minds believed in Vulcan, and for good reasons. Which begs the question, what ideas do we hold as unchalleneged truth that might later turn out to be false? And how harshly should we judge people in the past for explaining their world in the only terms they knew how?

The book is also kind of an ultra-condensed introductory overview of physics from Newton to Einstein. Not that I completely understand all of it, even after reading this. Unlike Einstein, I have basically zero intuition about physics (especially once we start talking about four dimensions) and I’ll admit as much. So if I could make it through this book, you can too. It’s definitely a popular science book and not at all dry or academic.

Appropriately for 2017, The Hunt for Vulcan has several historical accounts of total solar eclipses (since there’s really no other time that you can even try to observe something orbiting that close to the sun). Then as now, people traveled hundreds of miles to get to the path of totality. Unfortunately I wasn’t in the path of totality for 2017’s eclipse, and couldn’t get away to get there. But I will be damn close to the one in 2024, so I sense a trip to VT or upstate NY is in my future. (Just a reminder, the 2024 path of totality goes right over Niagara Falls. If you are a hardy enough soul to brave that traffic hell, I commend you, and godspeed.)

Levenson also peppers the book with historical anecdotes. The funniest were from Edison’s trip to see the 1878 total eclipse in Wyoming – the city boy not only met some colorful (and less than sober) locals, but was tricked into shooting a stuffed jackrabbit. Some of the serious ones concerned Einstein’s disgusted reaction to his colleagues’ overdone pro-German nationalism during World War I. (I wish Einstein’s thoughts didn’t sound so chillingly relevant at the moment.) Another interesting factoid is that Einstein’s colleague Erwin Freundlich, who was in Crimea trying to observe yet another solar eclipse when war was declared between Germany and Russia, was one of the first prisoners exchanged during the war.

Finally, I just couldn’t pass up the opportunity to share one of my all-time, hands-down favorite pieces of music in the world: The Planets by Gustav Holst. The Planets is inspired by the planets’ mythological meanings, of course, not anything to do with science. But having been composed between 1914-1916, it falls in an interesting historical window relevant to The Hunt for Vulcan. Einstein finally accounted for Mercury’s orbital irregularities in 1915; Pluto was discovered in 1930. Therefore The Planets includes neither Vulcan nor Pluto. And now, after Pluto’s “demotion,” The Planets still includes the “correct” number of planets. I think Holst was on to something, you guys.

So without further ado, Mercury, the Winged Messenger – since Mercury was the cause of all the hullaballoo in the first place.

Advertisements Share this: