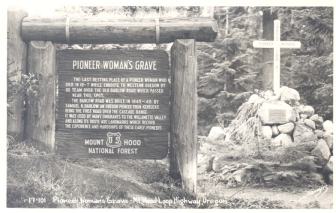

Before Charity Lamb was part of “one of the most cold-blooded and atrocious scenes ever enacted in Oregon,” she and her husband Nathaniel Lamb were pioneers on the Oregon Trail. They were headed to homestead in Clackamas County, Oregon, near modern-day Oregon City. Along the way, Charity gave birth to her fourth son. She read and wrote, which was uncommon for poor women Homesteaders in 1854. She was also a skilled seamstress, making beautiful dresses for fancy women in Portland.

But what truly set Charity apart was that she was first person to be convicted of murder, the first female prisoner, and later the first female asylum patient in the Oregon territory.

(As a side note, I tend to not write about murder or those sorts of things on this blog because I don’t want to perpetuate the stigma of people with mental illness being violent. But the reality is that the two are often conflated. I just wanted to mention that once again, I do not like to romanticize these things, but the intriguing nature of this case and what it said about society in the late 1800s was too fascinating to not write about).

No photos were available of Charity Lamb but here is a stock photo of a couple on the Oregon trail.

The Oregon Weekly Times, Oregon Spectator, and Oregonian newspapers all called her “a monster.” Certainly the irony of her name wasn’t lost on opinion columnists of the early 1900s who queried: “is it possible that some subtle or malign influences causes people to cultivate qualities opposite of what their verbal designation would seem to indicate them to be?”

But the true question is who did Charity kill and what was her motive? There are several highly sensationalized and fictionalized versions of the murder.

But the true question is who did Charity kill and what was her motive? There are several highly sensationalized and fictionalized versions of the murder.

The blog Off Beat Oregon wrote: “For many years, the case of Charity Lamb was looked at like a crime-fiction yarn from a pulp magazine like Spicy Detective. It seemed to have it all: illicit sex, a mother-daughter love triangle, conspiracy — and, of course, a brutal ax murder committed by a woman with the most ironically innocuous name imaginable.”

A pop-historian named Malcom Clark Jr. wrote a book called Eden Seekers, claiming that Charity and her 17-year-old daughter were both in love with the same man. In Eden Seekers, Clark wrote: “When (Nathaniel) Lamb, as outraged father and cuckolded husband, strongly protested, Charity cut off his objections with an ax.” Other journalists even called Charity a “faithless wretch.”

Charity’s son Abram testified, “He said that she had better not fun off, for if she went when he was away he would follow her and settle her when she didn’t know it. I heard her say that morning, before I went out with Pap hunting, that he was going to kill her and she didn’t’ know what to do.”

Here are the historically verified facts. Charity Lamb, Wife and Mother of Five Convicted of Murder for Killing Children’s Father. Let’s try this again and see how even facts can be molded to influence and shape opinion. Victim of Domestic Violence Convicted of Murder by All-Male Jury for Defending Self and Children Against Abuser.Unfortunately, self-defense wasn’t considered a legal defense yet. Hell, women weren’t even women allowed to serve on a jury in the 1850s. (Side note, women weren’t allowed to serve on juries in all 50 states until 1973). Charity’s lawyers argued that she had gone temporarily insane at the time of killing her husband. Two of their children Mary Ann (19) and Abram (13) testified that their father had often beaten, punched, and kicked her. Their father struck Charity with a hammer in front of the children, cutting a gash in her forehead. When she tried to leave, he held her at gunpoint.

After the children testified, some people’s attitudes towards Charity softened and the verdict was reached for second-degree murder, sentenced to life in prison. The prosecution had tried to convict her of first-degree murder, which would have sent her to the gallows, but her defense claimed that she only meant to maim her husband, not kill him. Meanwhile, her five children were sent to foster care.

Her legal defense also tried to plea for insanity. Although the jury denied the plea for insanity, she was probably considered insane by standards of that era for killing the father of her children, especially right at the dinner table with an ax. Later, she was transferred from jail to the Oregon State Insane and Idiotic Asylum in Portland.

There were possible political motives for this move too. With Charity moved to the asylum, Oregon would no longer have any female prisoners and face less scrutiny from other states.

Charity lived in the asylum for nearly twenty years, during which 1349 other patients were routinely received and treated. It is thought that Charity’s children visited her, as they testified in her support and supposedly empathized with her condition. Charity spent the rest of her life at the asylum.

What I found disturbing in researching this case was the fact that some blogs and articles, like Offbeat Oregon said that Charity and Nathaniel had a “stormy relationship.” And while I obviously wasn’t there and do not have ties to the family, actual historical accounts that I have read sicken me that somebody not call this exactly what it was: domestic violence. The blog goes on to say “It seems that Nathaniel didn’t intend to kill his wife, even if he wanted to.”

In any event, Charity Lamb, Oregon’s first female mental patient, spent the rest of her life in the asylum. She never had any problems with violence or outbursts, required any restraints or intervention with staff. She lived a peaceful existence supposedly knitting and helping out with chores around the kitchen until she died in her 60s.

In any event, Charity Lamb, Oregon’s first female mental patient, spent the rest of her life in the asylum. She never had any problems with violence or outbursts, required any restraints or intervention with staff. She lived a peaceful existence supposedly knitting and helping out with chores around the kitchen until she died in her 60s.

Charity is supposedly buried at the Lone Fir cemetery in Southeast Portland in an unmarked grave.

Sources cited:

Clark, Malcolm Jr. Eden Seekers: The Settlement of Oregon. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981

Lansing, R. (2000). The Tragedy of Charity Lamb, Oregon’s First Convicted Murderess. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 101(1), 40-76. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20615026

Offbeat Oregon. https://offbeatoregon.com/1511e.charity-lamb-murder-367.html

Sharing is caring: